|

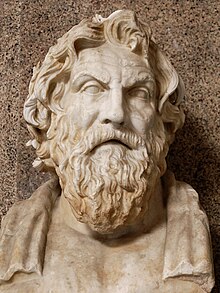

Antisthenes

Antisthenes (/ænˈtɪsθɪniːz/;[2] Ancient Greek: Ἀντισθένης, pronounced [an.tis.tʰén.ε:s]; c. 446 – c. 366 BCE)[1] was a Greek philosopher and a pupil of Socrates. Antisthenes first learned rhetoric under Gorgias before becoming an ardent disciple of Socrates. He adopted and developed the ethical side of Socrates' teachings, advocating an ascetic life lived in accordance with virtue. Later writers regarded him as the founder of Cynic philosophy. LifeAntisthenes was born c. 446 BCE, the son of Antisthenes, an Athenian. His mother was thought to have been a Thracian,[3] though some say a Phrygian, an opinion probably derived from his sarcastic reply to a man who reviled him as not being a genuine Athenian citizen, that the mother of the gods was a Phrygian[4] (referring to Cybele, the Anatolian counterpart of the Greek goddess Rhea).[5] In his youth he fought at Tanagra (426 BCE), and was a disciple first of Gorgias, and then of Socrates; so eager was he to hear the words of Socrates that he used to walk daily from the port of Peiraeus to Athens (about 9 kilometres), and persuaded his friends to accompany him.[6] Eventually he was present at Socrates' death.[7] He never forgave his master's persecutors, and is said to have been instrumental in procuring their punishment.[8] He survived the Battle of Leuctra (371 BCE), as he is reported to have compared the victory of the Thebans to a set of schoolboys beating their master.[9] Although Eudokia Makrembolitissa supposedly tells us that he died at the age of 70,[10] he was apparently still alive in 366 BCE,[11] and he must have been nearer to 80 years old when he died at Athens, c. 365 BCE. He is said to have lectured at the Cynosarges,[12] a gymnasium for the use of Athenians born of foreign mothers, near the temple of Heracles. Filled with enthusiasm for the Socratic idea of virtue, he founded a school of his own in the Cynosarges, where he attracted the poorer classes by the simplicity of his life and teaching. He wore a cloak and carried a staff and a wallet, and this costume became the uniform of his followers.[6] Diogenes Laërtius says that his works filled ten volumes, but of these, only fragments remain.[6] His favourite style seems to have been dialogues, some of them being vehement attacks on his contemporaries, as on Alcibiades in the second of his two works entitled Cyrus, on Gorgias in his Archelaus and on Plato in his Satho.[13] His style was pure and elegant, and Theopompus even said that Plato stole from him many of his thoughts.[14] Cicero, after reading some works by Antisthenes, found his works pleasing and called him "a man more intelligent than learned".[15] He possessed considerable powers of wit and sarcasm, and was fond of playing upon words; saying, for instance, that he would rather fall among crows (korakes) than flatterers (kolakes), for the one devour the dead, but the other the living.[16] Two declamations have survived, named Ajax and Odysseus, which are purely rhetorical. Antisthenes's nickname was The (Absolute) Dog (ἁπλοκύων, Diog. Laert. 6.13) [17][18][19] Philosophy According to Diogenes LaertiusIn his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers Diogenes Laertius lists the following as the favourite themes of Antisthenes: "He would prove that virtue can be taught; and that nobility belongs to none other than the virtuous. And he held virtue to be sufficient in itself to ensure happiness, since it needed nothing else except the strength of spirit. And he maintained that virtue is an affair of deeds and does not need a store of words or learning; that the wise man is self-sufficing, for all the goods of others are his; that ill repute is a good thing and much the same as pain; that the wise man will be guided in his public acts not by the established laws but by the law of virtue; that he will also marry in order to have children from union with the handsomest women; furthermore that he will not disdain to love, for only the wise man knows who are worthy to be loved".[20] EthicsAntisthenes was a pupil of Socrates, from whom he imbibed the fundamental ethical precept that virtue, not pleasure, is the end of existence. Everything that the wise person does, Antisthenes said, conforms to perfect virtue,[21] and pleasure is not only unnecessary, but a positive evil. He is reported to have held pain[22] and even ill-repute (Greek: ἀδοξία)[23] to be blessings, and he said, "I'd rather be mad than feel pleasure".[24] However, it is probable that he did not consider all pleasure worthless, but only that which results from the gratification of sensual or artificial desires, for we find him praising the pleasures which spring "from out of one's soul,"[25] and the enjoyments of a wisely chosen friendship.[26] The supreme good he placed in a life lived according to virtue — virtue consisting in action, which when obtained is never lost, and exempts the wise person from error.[27] It is closely connected with reason, but to enable it to develop itself in action, and to be sufficient for happiness, it requires the aid of Socratic strength (Greek: Σωκρατικὴ ἱσχύς).[21] PhysicsHis work on natural philosophy (the Physicus) contained a theory of the nature of the gods, in which he argued that there were many gods believed in by the people, but only one natural God.[28] He also said that God resembles nothing on earth, and therefore could not be understood from any representation.[29] LogicIn logic, Antisthenes was troubled by the problem of universals. As a proper nominalist, he held that definition and predication are either false or tautological, since we can only say that every individual is what it is, and can give no more than a description of its qualities, e.g. that silver is like tin in colour.[30] Thus, he disbelieved the Platonic system of Ideas. "A horse I can see," said Antisthenes, "but horsehood I cannot see".[31] Definition is merely a circuitous method of stating an identity: "a tree is a vegetable growth" is logically no more than "a tree is a tree". Philosophy of language Antisthenes apparently distinguished "a general object that can be aligned with the meaning of the utterance" from "a particular object of extensional reference". This "suggests that he makes a distinction between sense and reference".[32] The principal basis of this claim is a quotation in Alexander of Aphrodisias' “Comments on Aristotle's 'Topics'” with a three-way distinction:

Antisthenes and the CynicsIn later times Antisthenes came to be seen as the founder of the Cynics, but it is by no means certain that he would have recognized the term. Aristotle, writing a generation later refers several times to Antisthenes[34] and his followers "the Antistheneans",[30] but makes no reference to Cynicism.[35] There are many later tales about the infamous Cynic Diogenes of Sinope dogging Antisthenes' footsteps and becoming his faithful hound,[36] but it is similarly uncertain that the two men ever met. Some scholars, drawing on the discovery of defaced coins from Sinope dating from the period 350–340 BCE, believe that Diogenes only moved to Athens after the death of Antisthenes,[37] and it has been argued that the stories linking Antisthenes to Diogenes were invented by the Stoics in a later period in order to provide a succession linking Socrates to Zeno via Antisthenes, Diogenes, and Crates.[38] These tales were important to the Stoics for establishing a chain of teaching that ran from Socrates to Zeno.[39] Others argue that the evidence from the coins is weak, and thus Diogenes could have moved to Athens well before 340 BCE.[40] It is also possible that Diogenes visited Athens and Antisthenes before his exile, and returned to Sinope.[37] Antisthenes certainly adopted a rigorous ascetic lifestyle,[41] and he developed many of the principles of Cynic philosophy which became an inspiration for Diogenes and later Cynics. It was said that he had laid the foundations of the city which they afterwards built.[42] Notes

References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Antisthenes. Wikiquote has quotations related to Antisthenes.

|

||||||||||||||||||||