|

Miguel Enríquez (privateer)

D. Miguel Enríquez [nb 1] (c. 1674–1743), was a privateer from San Juan, Puerto Rico who operated during the early 18th century. A mulato born out of wedlock, he was a shoemaker by occupation during his youth. After working for the governor as a salesman Enríquez was recruited to defend Puerto Rico, then a colony of the Spanish Empire. He commanded a couple of guarda costas, receiving a letter of marque and reprisal from the Spanish Crown for his performance. Operating during the height of the Golden Age of Piracy, Enríquez's fleet was also credited with controlling the proliferation of buccaneers in the region. However, he was considered a pirate himself by the merchants of other nations, since it was common practice of the government to ignore when foreign ships were attacked.[2] Employing a systematic approach, Enríquez was able to become the most successful and influential Puerto Rican of his time and one of the most powerful men in the New World, converting San Juan into one of the best supplied and important ports in the Caribbean.[3] During his years as a privateer, Enríquez established close links with the Spanish Monarchy.[4] In the Caribbean he rallied the support of the Catholic Church, the Spanish bureaucrats and the foreign governors of St. Thomas and Curaçao.[5][6] Among other tactics, he used his ships for the distribution of urgent messages that arrived at San Juan or La Aguada to the rest of the Antilles.[4] When there was a shortage of royal vessels, Enríquez's fleet was responsible for transporting items on behalf of Spain without charge.[4] For this, the Crown granted him a Royal Auxiliary Identification Document (Spanish: Real Cédula Auxiliar), which allowed him to directly seek help from the Council of the Indies regardless of how insignificant a conflict was.[7] His ships also provided transportation for the authorities that arrived at Puerto Rico en route to other locations and for Catholic missionaries.[4] Throughout the War of the Spanish Succession, Enríquez's fleet was responsible for guarding the Spanish West Indies from incursions by the British and Dutch.[8] In 1717, Enríquez led an operation that expelled foreign settlers from Vieques, for which he was commended. His fleet also participated in other military expeditions in 1728 and 1729. Enríquez received several recognitions and exemptions that facilitated his work and contributed towards his vast wealth. Under the order of King Philip V (1683–1746), he was awarded The Gold Medal of the Royal Effigy (Spanish: "Medalla de oro de la Real Efigie") in 1713 and was named Capitán de Mar y Guerra y Armador de Corsos (loosely translated as Captain of the Seas and War and Chief Provider to the Crown Corsairs).[9][10] His success also led to resentment and constant clashes with the white caste of San Juan, placing him at odds with most of the colonial governors assigned to Puerto Rico. By the time that Matías de Abadía arrived to La Fortaleza, Enríquez was unable to accomplish his removal from office.[11] He was charged with smuggling and stripped of all his power and wealth by the government. Enríquez fled and took refuge in a Catholic convent. The charges of smuggling made by the authorities were eventually dropped, but he chose to remain in the premises where he died a pauper.[12] By the time that his career was over, Enríquez had commanded a fleet of over 300 ships, of which approximately 150 were lost, employing close to 1,500 sailors.[13] Early lifeEnríquez was born in San Juan to a poor family. The actual year of his birth is not clear due to contradictory dates, but the dates of 1674, 1676, 1680 and 1681 are referenced or recorded in official documents.[14] Most of these variations were provided by Enríquez himself, who would report a younger age when questioned. Of those proposed, 1674 seems more likely.[14] He was born to Graciana Enríquez, a freed slave of the same social hierarchy who had inherited the surname "Enríquez" from her former slaver, Leonor. His maternal grandmother was born in Africa, with Angola and Guinea being mentioned[15] while his maternal grandfather was an unknown white man. The name of Enríquez's father is not mentioned in any documentation, with the possible reasons for this being various and unexplored in the surviving records.[16] It is possible that either the identity was truly unknown by the public or that the father was a member of the Catholic clergy, which would have prompted a "silence pact" to avoid a scandal.[16] The second theory is supported by the fact that a member of the elite class, Luis de Salinas, served as the godfather of his brother, José Enríquez, despite the fact that he was also considered an illegitimate child.[17] It seems likely that both Miguel and José shared the same father.[17] Enríquez also possessed several sacramental objects and books written in Latin, which was a language only used by the clergy, now considered to have been inherited from his father.[17] He was the youngest of four siblings, the others being María and Juan. José died soon after his birth, before reaching his first year.[18] They lived in the room of a house belonging to Ana del Rincón on San Cristóbal y la Carnicería Street.[18] Unlike most children of the time, Enríquez was taught how to read and write at an advanced level, sufficient to compose detailed documents.[18] His writing style was elegant and he knew cursive, implying that it was a product of extended schooling.[18] By age 10, Enríquez had begun to work as an apprentice shoemaker. As a consequence, he also learned how to craft leather.[19] As was the custom during this age, Enríquez was enrolled in the military at the age of 16.[20] These units were divided by social hierarchy, with him serving under Captain Francisco Martín along other mulatos.[20] As a shoemaker, he would only earn four and a half reales per shoe pair.[21] Enríquez never married, but was known to have been involved with several women throughout his life, including Elena Méndez, Teresa Montañez, María Valdés and Ana Muriel.[22] Product of these relations, he had at least eight children, among which were Vicente and Rosa.[23] Of them, Enríquez preferred Vicente, raising him and overseeing his education .[23] In 1700, aged 26, he was accused of selling contraband in his house. This merchandise was product of trades where people incapable of paying with money, handed items in exchange.[19] The governor sentenced him to a year of forced labor in Castillo San Felipe del Morro and added a fine of 100 pieces of eight.[24] He did not deny the charges, paid the coins without any hesitation and his sentence was changed, upon his own request.[24] Enríquez was now sentenced to serve in the artillery of the Elite Garrison Corps. According to a witness, this change was facilitated due to requests made by influential members of San Juan's society, including some members of the Catholic Church.[24] With his job as a shoemaker, it is unknown how he was able to afford the fine so quickly, but it is assumed that he received help.[21] As part of the sentence, Enríquez could not charge for his work in the military, which also meant that during this timeframe he was economically supported by a third party.[21] Privateering careerIndependent work and letter of marqueMaterial documenting his early incursion in the business world are scarce.[25] In 1701, Enríquez began working as a salesman for governor Gutiérrez de la Riva.[26] It was under this governor that he would go on to become a privateer.[25] Like those that preceded him, Gutiérrez was appointed due to his military experience and his inauguration coincided with the War of the Spanish Succession arriving with a direct order to evaluate the cost of building a new vessel to "extinguish the commerce of [...] foreigners" that had reportedly engaged in piracy and other acts that threatened the Spanish economy.[27] Within a month, he responded with a report suggesting a system that operated between privateers and a ship to guard the coasts.[27] Both the geopolitical environment and the economic difficulty of the colony made privateering a successful and lucrative venture, both for the individual and for the government itself.[28] Gutiérrez proposed the construction of a new boat for the sole purpose of plundering enemy ships, with half of the loot destined to the Crown and the remainder being distributed among the crew.[27] This initiative was accepted and by 1704 the process was underway, with the ship being completed in 1707.[29] Gutiérrez needed a front man for this operation and Enríquez was eventually selected, his race allowing for a safe scapegoat if the privateering resulted in conflicts between the local government and Spain.[30] He proved successful in this venture and within a year his role had grown. Only two years after Gutiérrez took office, Enríquez already served as the governor's delegate and owner of vessels under his command.[30] These first actions were done independently, albeit with the government's compliance.[30] However, by 1704 Enríquez was already being listed as a privateer, receiving an official letter of marque.[30] His move from a salesman to an influential merchant and privateer was unusually fast, despite the experience that he had acquired during his time working for the governor.[31] Gutiérrez was instrumental in accelerating the success of the privateering venture, even allowing him access into a monopoly that he had created to run the local commerce through front men.[31] Based on these actions, it is possible that the governor mentored Enríquez personally, providing him with resources.[32] Multiple invasion attempts by enemy countries further fueled privateering operations, the Spanish West Indies were constantly being besieged by England, Denmark and the Netherlands.[33] The Spanish Crown did not take these threats lightly and ordered Gutiérrez to prepare for an hypothetical scenario, which ultimately proved to be a false alarm.[33] Despite the outcome, this mentality lingered, facilitating the war acts of the privateers. A year later, England actually tried to unsuccessfully invade Puerto Rico, landing within the vicinity of Arecibo.[34] With the War of Succession repercuting in the Caribbean, the actions of Enríquez were seen in a positive light.[35] Soon afterwards, French corsairs arrived at San Juan as allies, protected by the Crown with orders to be cared for.[35] However, these foreign vessels were being used to import contraband, which combined with a general animosity due to previous conflicts between these nations, further fueled the need to stabilize the economy by supporting local privateers.[36] On July 23, 1703, Gutiérrez died in San Juan.[36] Despite his connection, Enríquez was generally ignored by the members of the elite that opposed his rule and the privateering operation continued.[37] Gutiérrez's death brought forth a period of instability of five years, during which Puerto Rico had nine governors.[38] This favored Enríquez, who continued to thrive in the shadows. Most of them were simply interim governors and due to their short time in office, none were able to pay any attention to his growing success.[39] When Pedro del Arroyo was sworn, Enríquez tried to buy his favor by paying the voyage.[40] However, Arroyo died shortly afterwards, preventing a notable profit from this partnership.[40] Despite this, Enríquez actually paid for the funeral service and even provided the black clothing for the servants.[41] Despite his distinction, the former governor was not economically stable and his family was moved into the privateer's house.[41] One of the late governor's sons, Laureano Pérez del Arroyo, lived with him until his adulthood, when Enríquez requested that he was promoted to the rank of captain.[42] In time, Pérez del Arroyo would become of his most vocal enemies.[42] Eventually, as his wealth and influence grew Enríquez inherited some of Gutiérrez's old enemies, including the high class Calderón family.[37] Constantly serving the Crown, he quickly became the top privateer in Puerto Rico.[43][44] In a letter sent on February 14, 1705, the work done by two ships owned by Enríquez in the waters of Puerto Rico and Santo Domingo is praised.[45] King Phillip V expressed satisfaction and encouraged the continuation of this labor, not without claiming the weapons captured from his victims.[46] In 1707, Enríquez requested to be placed in charge of a company based there or in the adjacent locales of Havana or Cartagena.[39] The War Board of the Indies ignored his request, and some members even argued that to extend his stay in Puerto Rico he should only be recognized as Captain of the Sea, instead of the higher title of Captain of the Sea and War.[47] The authorities could not jeopardize the success attained by Enríquez's privateering fleet, which has gathered positive feedback from the local government.[47] However, they could not reward his efforts with a lesser title either. Following a heated debate, the Board decided to grant him the title of Captain of the Sea and War.[48] Enríquez actually planned this outcome, organizing his local influence so that the communications that reached the Crown were largely positive.[49] This correspondence was being sent years before this, by 1705 these letters were granting him the responsibility for controlling contraband and pirates in the coasts of Puerto Rico.[50] Caballero and Captain of the Land and SeasWith the delay or failure to arrive of the Real Situado, the governors were forced to collect money from the wealthier residents to make do.[51] Enríquez loaned money to the government since 1705 and noted this when issuing his requests.[52] He was officially recognized as Captain of the Sea and War on July 11, 1710.[48] By then Enríquez had become notably active in defending both Puerto Rico and the other Spanish interests in the Caribbean.[51] His privateering fleet had become such a key to local stability that they were the ones responsible for safeguarding the residents when storms or famine struck the island.[52] He continued to loan money to the government, advancing a sum of 11,497 pieces of eight between 1708 and 1712.[52] By 1708, Enríquez had become a renowned man, gaining the attention of Phillip V himself due to his work.[53] That same year, one of his ships brought the loot of a British vessel captured off Tortola to the port of Cumaná.[53] The authorities forced the privateers to sell the cargo in their port and retained two thirds of the earnings.[53] Enríquez was angered by this development and contacted the king, who responded by ordering a full restitution.[53] After five years of instability, the Crown appointed a sailor and merchant named Francisco Danío Granados as governor of Puerto Rico.[54] It is possible that Enríquez already knew him through Gutiérrez, who purchased merchandise from his company.[55] Like those that preceded him, Danío wanted to quickly gain a profit. As a dominant local merchant, this appointment would normally threaten Enríquez, but it seems likely that he was involved to some degree in the election process.[55] He went on to donate 4,000 pieces of eight before Danío' was sworn into office and provided an additional sum of 300 as a gift.[55] Two months before the new governor took office, the vessel ordered during Gutiérrez's term docked at San Juan.[40] Danío quickly tried to recruit a crew for it, but was largely ignored by the Puerto Rican sailors, who could earn a better profit by working independently as privateers.[56] Furthermore, Enríquez likely felt that this would affect his business and conversely sabotaged the recruitment.[56] This convinced Danío to order it to sail to Cartagena in search of a crew, which later mutinied during the return trip forcing a change in course that ultimately led to the vessel being lost.[57] With this struck of luck, Enríquez's business was now secure and he quickly pursued the favor of the governor, forming a mutually beneficial alliance.[57] Under these circumstances, Danío formed a pseudo-commercial alliance with the privateer.[57] On occasion, they staged the capture of a vessel so that merchandise could be sold without taxes or restrictions.[57] With mutual complicity, they then shared the profit in even halves.[57] However, any losses would fall on Enríquez. The corsair went as far as paying some of the governor's debts and helping members of his family.[58] These actions costed Enríquez money and men, but for some time served their goal of earning him the favor of Danío.[59] The privateering business continued to grow under this model. Enríquez continued to strengthen his reputation locally, taking over the cost of repairing the fortifications and supplying the military hospitals.[60] Enríquez pursued the rights to become the Royal Guinea Company sole representative in Puerto Rico. Established in 1701, this entity served as a major slave trader and became the only one sanctioned by the Spanish Crown to do business in their American colonies.[61] On May 16, 1710, he officially completed this goal, signing a loan contract with the company's general director, Juan Bautista Chouirrio.[26] With this accord, Enríquez became a major slaver in the territories of Puerto Rico, Trinidad, Margarita, Cumaná, Cumanagoto and Maracaibo, also permitting the acquisition of slaves from adjacent islands such as Jamaica, St. Thomas and Curaçao depending on convenience.[26] Under this agreement, he was able to import 40 African slaves per year, which he could sale under his own criteria.[26] The contract lasted for three years and it also provided exemptions for clothes and maintenance.[26] With the liberty to purchase these from any port in the Caribbean without right charges, it is likely that this was further exploited to import products at cheap prices, providing a large margin of profit.[62] For every peça sold, Enríquez paid 100 pieces of eight, which were combined with an additional fee of 4,000 per year.[63] Danío was involved in the transaction (which would also prove convenient for him as an official of the company) and along the other parts, an accord to secure that wins and losses were divided into three equal parts between them.[63] Enríquez was jubilant with this development and proposed public celebration to commemorate it.[63] He held the contract for a period of four years, leading 19 voyages under the premise of acquiring slaves and maintenance for them. Most of them were destined to St. Thomas. However, only ten of these incursions returned with new slaves for a total of 96, the others were used to import 109 barrels of flour.[63] This cereal was supposedly bought to feed his slaves, but instead it was sold to the wealthier classes for profit.[62] It is presumed that other odd products acquired under this premise, such as wine, beer, sugar, aguardiente, cocoa, paper and even copper, were sold in similar fashion.[64] His enemies were quick to publicly denounce this practice, albeit with some exaggeration.[64] Years later, these rights were supplanted despite the protests of Enríquez.[65] In 1713, the Royal Guinea Company lost its status and was instead replaced with the Royal Asiento de Inglaterra.[65] Enríquez immediately pursued a position within this new entity and quickly coordinated moves with some friends, Santiago Gibbens in St. Thomas and Felipe Henríquez in Curaçao, to establish a new business model once he acquired these rights.[66] To further secure the success of this venture, Enríquez offered gifts and even stakes to people that were already involved with the company.[67] In June 1718, attorney in fact Tomás Othey granted him the title of factor and completed a loan contract. Enríquez was only able to employ this office until September, experiencing a series of complications based on international politics.[68] During this timeframe, Othey himself imported slaves through the South Sea Company.[69] He took over as Puerto Rico's main supplier, both of food and military supplies, quickly becoming indispensable to the well-being and functionality of the government.[70] However, his tactics did not settle well with the higher classes, who began indirectly accusing him of bribery.[70] Despite this, the Crown was glad to accept any help, knowing that despite operating on for his own interests, Enríquez had become a vital figure in the Caribbean.[71] In 1712, Danío wrote to Phillip V requesting a recognition for these achievements.[71] The king consulted the Council of the Indies, which proposed that Enríquez should receive the Medal of the Royal Effigy (Spanish: "Medalla de la Real Efigie") which knighted him as a Caballero of Spain.[71] The award was officially presented on March 12, 1712.[72] This awoke the ire of the higher classes, who could not fathom how a mulato could receive such a recognition.[72] Enríquez was the first Puerto Rican presented with this distinction and also received the honorific of Don.[72][73] From this point onwards, this title preceded his name in any official documentation.[72] However, his adversaries intentionally avoided employing the honorific.[72] The following year, Enríquez was granted a Royal Auxiliary Identification Document, which allowed him to overcome the arbitrary restrictions that he encountered in some Caribbean ports.[74] This rare privilege shielded him from the authorities of the other Spanish colonies, redirecting any conflict to the tribunal of the Council of the Indies.[75] By the end of his five-year term, Danío had earned 55,179 pieces of eight, more than five times the amount that he would have earned by solely fulfilling his office.[58] By 1714, Enríquez had established working relationships with several merchants from non-Spanish territories.[76] Santiago Giblens and Felipe Henríquez remained his principal foreign associates.[76] By legal definition, the Crown recognized all of them as contrabandists.[76] To avoid this, Enríquez created a system that allowed him to import their merchandise while labeling it as privateering goods.[77] He ordered his associates to send loaded ships towards the open sea and with prior knowledge, sent one of his own to stage a capture.[77] Then the crew of his partner would safely return home in another vessel.[77] Enríquez took this approach with extreme precaution, asking that the letters discussing these plan should only be carried by a trusted person that could handle them personally.[77] To this ends, he employed his contacts within the Catholic Church and the captains of his ships, all of whom would protect him.[78] Besides this, the other parts were cautioned to avoid discussing these transactions even with close friends.[77] To ensure that they remained loyal, Enríquez often offered them gifts.[79] These were usually jewels or similar items, but on one occasion he returned a ship named La Anaronel, that had been captured by La Perla, back to the governor of St. Thomas to avoid conflicts with Giblens.[79] Enríquez secured this alliance by also offering a loaded vessel as a gift to his associate.[80] He rewarded his connections within the Church by importing items not found in Puerto Rico through these deals.[80] Furthermore, Enríquez requested that a jewelry in Barbados made several diamond rings, for both sexes, which he also used as gifts.[80] Silver shortage and feud with RiberaThe Situado was Puerto Rico's main source of silver coins, by dominating it Enríquez guaranteed complete control over the local market.[81] However, this move was complicated and the only way that he could accomplish it was by involving the governors and other royal representatives, forming a mutually beneficial endeavor.[81] He sold his privateering goods priced with Billon real coins, which were then used to pay the military.[nb 2][81] By the time that the silver coins of the Situado arrived to pay the military, they had already been paid and the silver was paid back to Enríquez.[82] By doing this he not only gained local dominance, but was acquiring a type of coin that would be accepted in all foreign markets.[81] However, this was not without problems, since the Situado was often late or incomplete, Enríquez would often face problems with liquidity.[82] In at least one occasion, this resulted in the confiscation of an account worth 4,000 pieces of eight.[83] Due to this, he experienced anxiety and would often issue letters requesting his associates to be patient and even requested credit until the silver arrived.[82] Tired of operating at a loss, Enríquez created a plan by himself. When the governor of Curaçao proposed an exchange of European goods, he employed Felipe Henríquez as his representative and the three of them evaluated the creation of a unique structure to acquire the desired silver.[84] The governor and Felipe would provide the capital, while he would employ his ships, the profits and losses would be shared equitably.[84] Enríquez would send one of his ships under the excuse of privateering, but in reality the vessel was going to dock at Curaçao and would load with European merchandise.[84] From there, the ship would travel to Veracruz, where the items would be sold as privateering goods in exchange for silver.[84] To hide this from view, the vessel would return to San Juan loaded with some merchandise.[84] The following voyage would be similar, albeit with a scale at La Guaira, where they would load with cocoa before traveling to Curaçao.[84] After traveling to Veracruz, they would only sell the European items, with the cocoa being introduced to Puerto Rico as privateering goods.[84] Enríquez expected to organize at least two yearly voyages under this format and even proposed the construction of a larger vessel, which would be boarded in the Curaçao scale.[84] However, the plan was brought to a halt with the arrival of the newly designated governor, Juan de Ribera.[85] On July 18, 1711, he was officially appointed by the king, but he could only take office when his predecessor's term was over.[86] Prior to arriving to Puerto Rico, Ribea and Enríquez exchanged friendly letters.[86] The privateer lowered his guard, expecting to have a productive relation with the future governor.[87] While exchanging letters, Enríquez spent over 20,000 pieces of eight as gifts and other considerations and even lent his best vessel, La Gloria, so that Ribera could arrive.[87] He also made sure that La Fortaleza was fitted with supplies to last several months.[88] Ribera arrived to San Juan on December 23, 1713, replacing Danío. Enríquez was confident that with his previous actions he had gained the governor's favor, but noticing that his ship arrived fully loaded likely offered an early warning that the functionary actually intended to compete with him.[88] Ribera had manipulated the privateer, projecting a benign posture to avoid waking any suspicion.[89] Having spent the two years after being appointed in the adjacent Cumaná and Margarita, the governor had observed the models used in the Americas and established connections, also becoming familiar with Enríquez's own modus operandi.[89] Shortly after taking office, Ribera attempted to eradicate privateering from Puerto Rico for his own benefit.[85] He quickly employed his connections in attempts to take over Enríquez's market.[90] After completing his first term, Danío left his entire fortune in charge of Enríquez, while he returned to Spain.[6] They agreed that the money would be sent there when needed. However, the arrangement was difficult, since the money was filtered by small quantities or failed to arrive at all.[6] Ribera would employ the privateer's own model against him, mimicking several of his tactics, albeit in a more aggressive fashion.[90] Considering Enríquez a direct adversary, the governor intercepted his mail and took over profitable associations.[91]

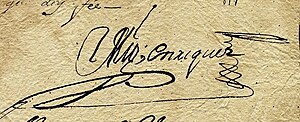

— Royal Decree from Philip V to Enríquez informing him of the destitution of Juan de Ribera, February 10, 1716.

Ribera systematically stripped Enríquez of his belongings, also launching a campaign to discredit him among Spanish merchants.[92] The governor took control of the shipyard and used it to construct a sloop, a brigantine and a schooner.[93] The animosity between both was fueled by the fact that no side was willing to recognize the authority granted to the other. On one occasion the governor asked him to certify (on behalf of the Royal Guinea Company) that a ship had not returned, after it arrived from St. Thomas loaded with an illegal haul, but Enríquez refused to commit fraud.[92] Due to the pressure involved, he was ultimately forced to do so. However, Enríquez visited the Secretary of Government, who served as a witness of the act.[94] The same occurred later with a ship that arrived from Trinidad, but this time he firmly refused, claiming that he was willing to risk his life if that meant conserving his honor.[94] During this administration, a new treasurer was appointed to Puerto Rico, José del Pozo Oneto.[95] Enríquez had tried to win the functionary's favor when he arrived, providing slaves and several other gifts.[96] The first year of his incumbency was nominal, however, in early 1717 a series of conflicts between them became apparent.[97] According to a witness account, these differences began when Enríquez refused to loan 4,000 pieces of eight that Pozo wanted for personal matters.[97] Another factor could have been that the treasurer owned several stores in San Juan and was competing with the privateer in auctions.[98] Eventually, Pozo sided with another man that was battling to gain power, dean Martín Calderón.[99] Throughout Ribera's term, the elite class of San Juan launched a disparaging campaign, offended by the fact that a mulato had essentially become the most influential figure in Puerto Rico.[100] They would constantly address the Spanish Crown and accused him of smuggling, a notable concern during the era, or attempted to disregard his privateering skills.[101] The high class group that led the campaign was the Calderón family, to which the dean belonged.[102] It is likely that these differences materialized years before, but that these groups were simply waiting for the opportune moment to act on them.[103] Despite their status, the Calderón family was notorious for being involved with contraband and Ribera allied with them to pursue his own goals.[104] The family even employed the influence of one of his members to create divisions between Enríquez and the newly arrived bishop Pedro de la Concepción Urtiaga.[105] He was able to counter these accusations following the arrival of a prelate that favored him, neutralizing their influence.[105] With the Calderón family on his side, Ribera decided to ignore all of the remaining families due to internal divisions.[105] The governor went as far as eliminating any group that may threaten his intentions of creating a commercial monopoly, grounding Enríquez’s fleet by denying permits and trying to enter the business himself.[105] The bishop quickly took notice and denounced these actions, avoiding the mail interception of the government.[106] After briefly considering a relocation to Santo Domingo, Enríquez launched a counterattack.[107] He proposed to the local authorities that they should speak on his behalf, accomplishing this through several figures, including Danío.[107] Ribera was accused of creating a contraband bank before the king, while accountant Antonio Paris Negro highlighted Enríquez's work.[108] These frequent letters began to tip the balance in the privateers favor, but time favored the governor.[109] Based on this, Enríquez granted Danío the rights to serve as his extra-official representative and provided him a vessel in which to travel to Madrid.[109] Ribera attempted and failed to block the voyage, but succeeded in stalling it and forcing an additional scale.[109] Once there, Danío acted to expose Ribera and pursued a return to office.[110] Locally, Enríquez convinced functionaries to send complaints devised by himself while portraying them as being personal.[110] Paris Negro was a prominent member of this initiative.[110] Furthermore, these letters were used to also accuse the Calderón family.[111] During the final months of 1715, the Council of the Indies was investigating Ribera, confirming that some of the complaints were real.[112] As a result, Francisco Fernández del Barco was assigned to evaluate his administration.[113] Ribera's anti-privateering politics were abolished. A few days after, Fernández issued two documents that secretly prepared the governor's eventually deposition.[114] The first was sent to the governor of Cumaná, José Carreño, and requested that he travel to Puerto Rico and execute the confiscation of Rivera's property and interests with the help of local authorities which was done on May 3, 1716.[nb 3][114] The governor was then to be held captive at La Fortaleza, without communication separated from any allies, being then transferred to a jail.[115] The second letter restituted all of the property that Ribera had stripped from Enríquez.[114] The prosecution was swift, only two months later Fernández arrived to San Juan, taking control of the charges.[116] Carreño took the office temporally, until the appointed interim governor arrived.[116] Ribera and his associates were charged with contraband and monopolizing the market, falsely gathering money for causes that never materialized and of exploiting the Situado, among other things.[117] He was sentenced to pay 40,317 pieces of eight and he was forced to pay an additional sum of 86,370 to Enríquez.[118] Afterwards, Ribera remained imprisoned in El Morro until a frigate named La Reina arrived to take him to Spain.[119] After only serving for nearly two years, the former governor was returned to Spain chained.[11] However, this ordeal had a considerable impact on Enríquez's fortune, which was further exacerbated by the fact that he decided to sustain his employees despite the fact that his fleet was not sailing.[120] Acquiring unparalleled wealthIn 1716, Enríquez made a suggestion to Carreño that they organize an expedition and take the island of Saint Thomas.[121] The interim governor sent an official proposal and noted his belief that the privateer and 500 militiamen would suffice and that no royal investment would be needed, but ultimately desisted of the idea after the project failed to gain approval.[122][121] Alberto Bertolano took the office of governor from Carreño, being sworn on August 30, 1716.[123] As usual, Enríquez tried to earn his favor.[124] However, due to his role as interim governor, Bertolano distanced himself from any of the groups that dominated the Puerto Rican society.[125] This approach did not please Enríquez, who went on to claim that his opponents, led by Pozo, were being favored.[125] An argument that was ironically repeated by them.[125] However, the governor was instrumental in helping Enríquez to resume his role as a privateer.[126] The War of the Quadruple Alliance hurt Enríquez's interest, since he was forced to surrender all of the property that belonged to the Real Asiento.[127] He declared that he no longer possessed anything that belonged to the company.[127] With the embargo taking an extended time period, Enríquez likely hid the Real Asiento's property during the wait and keep them for himself.[127] Pozo was not pleased with this outcome and requested the intervention of dean Martín Calderón, expecting the church to intervene.[128] Harassed by the ecclesiastical investigation, Enríquez requested a license permitting a move to Cuba, which was granted but never materialized.[128] The arrival of a new bishop, Fernando de Valdivia, prevented the migration.[128] Before leaving Spain, the friar had received requests to favor the privateer.[128] Enríquez paid the voyage and offered Valdivia all sorts of gifts, including a house, jewels and slaves, spending at least 3,000 pieces of eight.[129] For the next two weeks, the Bishop only had contact with the privateer, even ignoring the governor.[129] Valvidia eventually established a lukewarm relation with the authorities, which was always superseded by his friendship with Enríquez.[130] With his power, the Bishop revoked the actions of Matín Calderón and placed the blame of the conflicts on the dean and treasurer.[129] Ultimately, both sides continued to perpetually exchange accusations and insults.[131] Despite running a generally neutral administration, Bertolano was accused of being biased by both sides after his term concluded.[125] By focusing on his role as a merchant and exploiting legal loopholes about privateering spoils, Enríquez gathered so much merchandise that it was unrivaled in Puerto Rico, selling anything that covered basic necessities of the citizens, ranging from food to brushes, razors, leather, locks and clothes.[132] They also offered other commodities, such as playing cards, wines imported from Spain and equipment required for horse riding.[133] Enríquez managed four warehouses, which besides storing merchandise were also used to manufacture anything that his ships needed.[133] He divided them by class, separating the ones where food was stored from the ones where backup equipment was kept.[134] However, this model also had its drawbacks, since it was linked to the sort of relationship that he had with the authorities, with cities like Santo Domingo, Margarita and Santiago blocking him on occasion.[135] Despite the volatile nature of his business model, Enríquez managed to secure a massive fortune. In 1716, he personally quantified the amount that Juan de Ribera owed him at 86,370 pieces of eight, which added to 20,000 that he donated, would place his fortune in at least 106,370.[136] Fourteen witnesses claimed that based on the number of houses, haciendas, slaves, ships and amounts of other capital, his fortune should have surpassed at least 100,000.[135] Enríquez himself stated that by then it was over 150,000 pieces of eight.[136] Antonio Camino, who managed the money claimed that when all of the capital was added, the total ranged between 350,000 and 400,000.[137] Valdivia supported this assertion, noting that Enríquez's house contained more items than any other house in Puerto Rico, without including its warehouses.[136] Furthermore, his haciendas produced sugar cane, cattle and crops, which were lucrative ventures by themselves.[138] With growing contempt against him, Enríquez secured the well-being of his son by placing three houses in San Juan and a farm near Bayamón river (worth 20,000 pieces of eight) to the service of the church.[139] This move guaranteed that they would be beyond the reach of his enemies, with the intention that Vicente would end serving as the chaplain of these properties, receiving a stable income and inheriting at least part of his fortune.[140] To this end, he made a request to Valdivia so that Vicente could fulfill this role.[140] Despite this office, he would also aid his father manage his business.[141] Enríquez had also led an effort to rebuild the cathedral of San Juan.[142] Despite being of mixed race, Enríquez owned several African slaves, which served as an assertion of his social status and performed his menial tasks.[143] At least 50 were working in one of his haciendas, El Plantaje.[144] Enríquez owned another hacienda, Ribiera del Bayamón, where he employed 49 black slaves. Of which he might have fathered a significant portion of 21, which shared his last name, with most also being named Miguel.[145] The other option being that the parents of these children decided to adopt his name as a form of tribute for their master.[145] He maintained this group with three plantations that amassed over 7,982 plants and 10,000 yards where yuca was cultivated.[146] His haciendas were mostly dedicated to the support of his slaves, who in turn did most of the hard work that sustained his empire.[143] Enríquez employed more in his workshops and the port, performing works that varied from carpenters and blacksmiths to moving cargo and supply ships that were about to set sail.[144] Enríquez rarely bought these slaves and the few times that he did it was through the advantages provided by the Royal Asiento or the Guinea Company.[147] Most of them were actually acquired through his privateering vessels. Enríquez was the Puerto Rican that owned more slaves during his time and was reportedly harsh with them. His methods of discipline included holding them captive in his own private jail, food deprivation and flailing.[148] Between 1718 and 1720, several storms affected Puerto Rico, destroying the agriculture and causing a shortage of food and shelter.[149] To further complicate matters, an epidemic was declared, causing the death of several patients.[150] The residents of San Juan asked Enríquez to help, and he responded by donating 400 jars of melado (a type of food made from sugar and molasses) and an entire shipment of corn, which one of his ships had delivered.[150] He also took over the funeral services of the poor that died, paying the Church personally.[151] In 1720, the conflict with Pozo continued, when the treasurer noticed that Enríquez owed 2,986 pieces of eight in taxes he denounced it.[131] The Council of the Indies executed a secret investigation of the privateer, based on these allegations.[152] His years of loyalty to the Crown had been ignored by the king himself.[153] However, the process was delayed. Prior to this, Pozo had been even able to secure that his allies won the 1719 municipal elections, running a smear campaign against Enríquez to get them elected.[154] The process was plagued by irregularities, with viable voters being arbitrarily disqualified beforehand.[154] Second term of DaníoOn October 12, 1717, the Spanish Crown granted Danío a second term as governor of Puerto Rico.[155] This was a goal that he and Enríquez had originally planned since the end of his first administration.[156] However, with time the privateer lost interest, feeling that it was no longer necessary to secure his goals.[157] Danío did not take the office immediately since he was ordered to gather and equip a hundred soldiers that would accompany him.[158] The enemies of Enríquez panicked, fearing that the privateer would possess the support of the governor, bishop and accountant.[155] They soon launched an aggressive defamation campaign to revoke this appointment and seized as much control as they could before his arrival.[159] However, their initiative failed.[159] Enríquez and Danío had remained close following the first term, with one of his nephews receiving his education along Vicente.[23] However, the irregularity in the fulfillment of their previous agreement took a toll. Knowing this, Enríquez quickly tried to once again earn his favor through letters, directly accusing his adversaries of the breach of their accord.[160] Danío arrived to San Juan on April 6, 1720, and was immediately received by a belligerent Pozo, who told him that the privateers' enemies were now his own.[160] During the first months of this term, the governor actually persecuted this group.[161] Enríquez thrived, his fleet capturing four vessels, two from the Netherlands and one from Great Britain and France apiece.[162] Soon after, Danío began a trial of residence that seized the properties of Pozo, who had since gathered a considerable fortune.[163] The former treasurer was also jailed and permanently vanished from the New World.[164] Furthermore, Danío also managed to acquire ecclesiastic censorship from Valvidia, who threatened his allies with eternal damnation.[164] Twelve residents soon revealed the places were Pozo has hidden part of his wealth.[164] The governor used the law as his weapon, who sentenced the other involved to pay a fine of 1,601 pieces of eight and banned them from serving in a public office for a period of ten years.[165] Some were even banished from San Juan. Those affected quickly countered by sending letters to the Crown, which responded by ordering the excarteration of Pozo, allowing him to present his case in Spain.[166] However, before the former treasurer could do that, he found himself involved in the secret investigation that was being done against Enríquez.[166] Due to the large number of accusations offered by each side, the Council of the Indies suspected both.[167] Judge Tomás Férnandez Pérez was placed in charge and arrived to San Juan in 1721.[167] Danío was also involved due to his friendship with the privateer and he was ordered to cooperate with the investigation by leaving San Juan while it was underway.[167] Fernández began by interrogating 21 of Enríquez's enemies, who offered the same arguments.[168] Once the judge heard all of their versions, he determined that they were merely motivated by their desire to punish the privateer.[168] The blame fell on Pozo and Francisco de Allende, with the entire group being jailed.[169] Enríquez expected to emerge stronger from this process, however, his relationship with Danío quickly took a turn for the worst.[170] It is likely that the governor felt that the privateer was not willing to cooperate or help him during the investigation.[171] The remainder of Enríquez's enemies may have noticed this and pursued his favor, leaving Pozo and his faction alone.[171] During the course of the trial, the animosity between Danío and the privateer became evident.[172] The residents of San Juan were surprised, being familiar with their prior affinity.[172] None of them publicly declared the reason for the conflicts due to the contentious nature of the actions done during their partnership.[172] Under these circumstances, Enríquez found himself in a familiar position. With Danío's opposition, his privateering venture was endangered.[173] Once again Enríquez was forced to defend his role in the defense and supply of Puerto Rico from those that tried to minimize its importance.[173] Despite this, he was able to keep a number of vessels constantly active, being the owner of at least 20.[173] Enríquez did everything within his reach to keep a de facto monopoly over the local economy and despite the political tension, he was still turning a considerable profit.[174] Danío's first attempt to challenge this dominance was timid, he fomented more guarda costas and facilitated the emergence of new privateers.[174] Among them there was Miguel de Ubides, a vocal critic of Enríquez, who received the authorization to purchase a ship from the governor of Margarita.[174] Upon learning of this, the privateer quickly moved his connections.[174] Enríquez wrote to the governor of Margarita and requested that the ship was not sold to anyone from Puerto Rico.[174] Valvidia, who was also the bishop of Margarita, also interceded in his favor.[174] When Ubides arrived, he was told that the ship was no longer for sale.[174] He received the same response in the ports of Cumaná and La Guaira.[174] When two slaves were involved in an incident, they were imprisoned in Enríquez's private jail for a period of four months, until Danío ordered their release to antagonize him.[175] The governor also ordered the incarceration of Enríquez in Castillo San Felipe del Morro for cheering posters where the images of several powerful figures were satirized.[11] He did not deny these accusations, instead simply responding that celebrating their use did not damage anyone.[11] Meanwhile, the governors of Margarita and Cumaná also helped the privateers by issuing licenses of their own, which resulted at least in the capture of a British vessel.[176] Enríquez continued to perform favors for the Royal authorities, fixing their ship in his private shipyard and serving as a ferry for a variety of government and Church officials.[177] Later that year, Enríquez fell victim to two embargoes, where his properties remained confiscated until 1724.[137] However, the authorities were only able to seize what was registered in his name, with neither jewels or coins being listed in the official forms.[137] It is assumed that he his this portion of his fortune where they could not retrieve it.[137] From these documents it was established that he was the wealthiest Puerto Rican of his time, capable of casually investing 500 pieces of eight.[178] In San Juan alone, Enríquez owned 13 well-equipped houses, several of which he employed for other purposes such as warehouses, carpenter and mechanic shops, an armory and a blacksmith.[179] Another one served as a hotel for notable visitors, while a third one was used to temporally house the Catholic Bishops.[179] Most of them were located at Santa Bárbara street, adjacent to the San Justo marina.[179] His main house was one of the most complete 18th century houses on record and it was equipped with several luxurious decorations, including several pieces of art, but it was also partially converted into a warehouse and store.[180] This marked a stark contrast in a time where the government heavily depended on the Situado and the governor's salary was only 2,200 pieces of eight, while other high-ranking figures did not even reach 800 and common professionals barely reached 3 per day.[178] By 1723, Enríquez had developed a reputation for altruism, reportedly helping neighbors and foreigners alike.[149] On a yearly basis, he continued to work with charity, donating to treat the sick and providing clothes for the poor.[181] However, this actions did not sit well with his enemies, who made efforts to minimize their impact.[151] Despite these efforts, on a personal level Enríquez's grew to dislike the prospect of manual labor and adapted his clothing and diet to that of the higher class that attacked himself, expressing disdain when the only foods available were those commonly consumed by the poor.[182] In 1722, Enríquez alleged in a letter to the Spanish Crown that since his return Danío had only pursued the appropriation of his fortune and done corrupt actions that led to losses in his privateering ventures.[172] These accusations were backed by Valdivia and Paris.[172] However, the governor was likely simply trying to recover the wealth that he had left in charge of the privateer years before.[172] Enríquez tried to bring an end to the conflict by offering a sum between 15,000 and 20,000 pieces of eight to Danío.[183] However, this offering was declined.[183] Furthermore, both could never agree on the amount of money that was owed due to their previous arrangement, with the governor claiming that it was 42,261 pieces of eight, but the privateer rebuffing that it was a shared debt and that the fortune was spent in critical investments.[184] Enríquez even told the king that he possessed a document stating that he was actually the creditor of the governor's fortune and as such owned nothing.[183] This infuriated Danío, who ordered his incarceration on December 9, 1722.[183] Antonio Camino, was also jailed but soon escaped and traveled to Havana.[183] Once there, he began collecting positive accounts for his employer.[185] Among those that agreed to help were a group of military officials that had been neglected by Danío in October 1720, only to be fully attended by Enríquez.[185] After gathering the support, Camino traveled to Spain where he spoke in the privateer's behalf for over a year.[186] Valdivia tried to request an excarceration with external help, but Enríquez remained in jail.[186] The relationship between the Church functionary and the privateer had been criticized by Danío.[187] The governor tried to restart the official privateering project by himself, meeting moderate success by mimicking the pirate code's repartition of the loot captured.[188] They captured three vessels, two from France and Great Britain and a third one sailed by freebooters.[188] In Spain, Camino's testimony gained the attention of the Council of the Indies which suggested to the king that Danío was investigated and that a new governor should be named to eventually replace him.[189] Phillip V named José Antonio de Isasi .[189] The Council also requested the liberation of Enríquez and the restitution of his property.[189] However, this failed to materialize since Isasi remained in Spain for nearly a year after his appointment and by 1724 he surrendered the nomination.[190] The Council named Captain José Antonio de Mendizábal as his replacement.[190] While preparing, the military officer received strict orders to jail Danío and liberate Enríquez as soon as he arrived to San Juan.[190] As usual, the privateer also took the initiative to gain his favor.[191] On August 23, 1724, Mendizábal took the office of governor and only six days afterwards he ordered the incarceration of his predecessor.[191] In the end, Enríquez succeeded in bringing an end to Danío's second term.[11] He suffered the same fate of Juan de Ribera.[8] However, Danío's case dragged on for a prolonged time period, forcing him to remain captive in San Felipe del Morro until at least 1730. The former governor was subsequently transported to Madrid, where he remained in jail.[192] Enríquez provided transport to Danío's prosecutor, Simón Belenguer so he could return to Spain, but was unable to gain his favor.[193] This functionary criticized all of the involved and even argued that the privateer's actions were more akin to a pirate than to a military officer.[194] However, Belenguer placed most of the blame on Enríquez and issued harsher sentences to his allies that to his enemies.[195] Dean Martín Calderon and Pozo were declared free of guilt.[196] To justify his actions, Mendizábal conducted his own investigation.[192] During this process, even the former allies of Danío testified against him.[192] Later yearsFollowing Danío's trial, Enríquez received full support from Mendizábal.[197] The governor largely ignored Balaguer's sentence.[197] The Mendizábal administration became the most tranquil time period in Enríquez's career.[197] In Spain, Phillip V was briefly replaced by Louis I, only to return to the Crown.[197] The king quickly introduced a new politic that focused on Spain 's superiority in the Atlantic.[198] This created a new rift between the Empire and Great Britain, which directly benefited Enríquez.[199] The First Secretary of State, José Patiño, decided that the privateer's fleet would be employed towards this end.[200] This functionary archived all the complaints issued by his enemies, dismissing the efficiency of their work.[200] Enríquez's fleet defended the local trade, a difficult mission due to the proximity of St. Thomas to Puerto Rico.[201] During the summer of 1728, he was forced to attend a local enemy. Captain Isidro Álvarez de Nava and other members of the military were plotting to assassinate Mendizábal and the privateer.[202] Word of this reached the governor on June 26, 1728, but was largely ignored. Álvarez was the most experienced military captain and would take the office of governor in case of death.[203] He was also related to Fernando de Allende, who insisted that if Enríquez survived, the assassination would fail in turning the balance of power.[203] Two unsuccessful attempts were organized against the privateer.[204] A subsequent confession, offering full detail of the plot, put an end to it. The conspirators vehemently denied these accusations, claiming that Enríquez was framing them.[205] The governor negotiated with the soldiers and convinced them to submit to a temporary sentence in El Morro.[206] Afterwards, Álvarez was released and continued his defense at Madrid.[206] With his vessels playing a key role to secure Spain's dominance over Great Britain during the Anglo-Spanish War, Enríquez made a bold request for a mulato, asking Patiño to help him reach the rank of Royal Admiral.[207] The secretary never answered this petition.[207] The actions of Enríquez soon gained notoriety among the merchants affiliated to the South Sea Company, who gave him the nickname "The Grand Archvillain".[73] One of them once described him by saying "[Enríquez] has raised himself to be in effect King, at least more than Governor of Porto Rico (sic)".[73] Mendizábal's cooperation benefited both his business and his military influence, and the governor went as far as employing politics to favor him. On one night, a group of 23 slaves escaped from El Plantaje and were joined by some employees from his shipyard.[208] Consequently in May 1728, Enríquez ordered two of his ships to go to St. Thomas to reclaim the slaves that had escaped. He also ordered that if this could not be accomplished, they should go to the San Juan cays and capture as many as possible, which they did and returned with 24 slaves.[209] Taking notice, Mendizábal requested a treaty with Denmark that allowed the return or replacement of slaves that escaped between Puerto Rico and St. Thomas.[210] Despite being fully invested in the war effort, Enríquez also continued to serve the Crown in other aspects. His fleet was forced to secure the arrival of Cumaná's Situado, evading a British squadron.[211] Enríquez also continued providing transport to the authorities and even some civilians.[211] That same year, he sent Camino to Havana in order to complete a task.[212] However, Enríquez's confidant failed when he lost the relevant documentation, losing to a local privateer and costing a significant amount of money.[212] The privateer was angered by this development, Camino responded by reclaiming payment for his entire career and threatened that he would travel to Spain seeking retribution.[213] Enríquez's enemies considered this an opportunity to give credibility to their allegations.[213] However, as years went by the number of captured vessels became consistently smaller due to Spain's shifting its focus to the Mediterranean.[214] Enríquez also lost his influence within the Church with the arrival of a new bishop, Sebastián Lorenzo Pizarro, who declined any gift or favor that he offered.[215] After the war ended, the Empire's relation with Great Britain normalized, further complicating this venture.[214] Under these circumstances, the work of Enríquez served as an obstacle and by 1731, Mendizábal's last year in office, he was no longer considered a key asset in the New Word.[214] The sudden change in geopolitics combined with conclusion of Mendizábal's term began a downward spiral for Enríquez's life.[216] On October 11, 1731, Matías de Abadía docked at San Juan and took office a few hours later.[216] A military officer, Abadía was accompanied by three trusted men, who were quickly placed in the pivotal offices of treasurer of Puerto Rico, overseer and manager of the city.[217] Even before traveling to San Juan, the governor had orders to settle the constant conflicts between its residents.[218] Abadía was also placed in charge of attending Camino's case against Enríquez and of investigating the assassination attempts.[218] Following his intervention, the cases of Danío and Álvarez were suddenly re-evaluated by the Council of the Indies and Enríquez was forced to pay 4,000 pieces of eight to the former governor, despite the fact that the investigation had already been closed.[219] Álvarez was also released and reinstated in his military position, with the privateer being forced to pay again.[219] The influence that Enríquez once possessed was now wavering and he was likely being held accountable for the incidents of the previous decades.[219] His enemies exploited this and bishop Pizarro aligned himself with the governor, only contacting the privateer to order the use of his vessels for transportation.[220] The fact that Spain needed a scapegoat to appease the British government complicated his position.[221] His privateering venture systematically shrunk, until his last ship was decommissioned by the governor. Furthermore, knowing the lucrative nature of the practice, Abadía employed front men that worked as privateers for him.[222] Eventually, he decided to abandon privateering altogether.[223] During the final months of 1732, Abadía sentenced Enríquez for not paying Camino and another group of merchants.[224] The former was to receive 5,800 pieces of eight, the salary of ten years, despite the protest of the privateer who reclaimed what he had given to his former trustee.[224] Enríquez tried to appeal, but before a sentence was reached Abadía forced him to pay.[225] The privateer gave 20 slaves that were worth the fine.[225] Furthermore, Enríquez was forced to pay 21,631 additional pieces of eight for an unrelated matter.[225] The merchants were demanding 72,285 which Abadía also granted, despite the fact that Enríquez assured that the debt was paid.[226] The governor's stance led to the arrival of several alleged creditors, which in turn reclaimed their own purported debts, some dating back nearly thirty years.[226] Twenty-two cases were open for the total of 199,129 pieces of eight, 4 reales and 11 maravedís.[226] The Crown itself reclaimed 25,069 pieces of eight and 2 reales for a trade, equipment and the capture of a slaving vessel by La Modista.[227] The Church also demanded 27,291 pieces of eight based on three transactions.[227] In the end, even the totality of Enríquez's fortune would not be enough to pay the entire sum.[228] A complete embargo was ordered by Abadía in 1733.[220] Mysteriously, the entire fortune was only estimated to be worth 43,000 pieces of eight, although the worth of his slaves alone was known to surpass this sum and he had invested 150,000 recently.[228] Since his goods were insufficient to pay the debt, Abadía complied with the demands of Camino and seized the chaplaincies that were created by Enríquez's donation to the Catholic Church, leaving his son without a place to practice.[141] Vicente tried to appeal at the Royal Audiencia of Santo Domingo.[229] However, his plights were ignored and the governor's ruling was upheld. In 1734, Enríquez issued a complaint stating that Abadía was prohibiting him from using the title of Caballero of the Royal Effigy and requesting a confirmation of said title.[230] The Council of the Indies preferred to ignore the request, instead telling the privateer to show the relevant medal to the governor.[230] That same year, Abadía judged the Mendizábal administration and ordered the incarceration of the former governor, basing his entire case on the complaints of Pozo.[230] Enríquez was also involved in the prosecution, which focused on his supposed debts.[224] He tried to provide his own documentation, but the governor declined.[231] In May 1735, Vicente died, filling the former privateer with guilt.[229] Attempting to escape the administration of Abadía, Enríquez took refuge in the Convent of Santo Tomás on October 30, 1735. He remained there after hearing rumors that he was going to be jailed at Castillo San Felipe del Morro.[141] However, even there the governor pursued him. Abadía requested permission to obtain a search warrant and check if Enríquez had taken any wealth there.[229] All of the rooms were rummaged, but nothing of worth was found.[229] Despite this, Abadía confiscated Enríquez's correspondence.[229] Incredulous, the former privateer requested a certification for the search warrant.[232] Between 1735 and 1737, Enríquez wrote to Phillip V six times requesting an independent prosecutor that could launch a neutral investigation.[233] He also offered to reorganize the now scattered privateers.[233] However, the king never replied directly and the only response, issued by the Council of the Indies, informed him that they did not consider that action convenient.[233] From that moment onwards, Enríquez only wrote to detail his misery and to request the payment of an old debt.[234] During the following years, his only contact to the outside world was through the Dominican friars.[235] To Enríquez's chagrin, Abadía had unusual longevity in the office of governor, with the Crown granting him time beyond the stipulated five years.[236] In 1740, the Council of the Indies revised Mendizábal's case and issued a declaration restoring his honor and rank.[231] However, they never did the same for Enríquez, despite being charged as a supposed accomplice of the former governor.[231] Most of his friend eventually left, only Paris and the members of the Church remained besides him.[237] On June 29, 1743, Abadía died while still in office.[238] Five months afterwards, Enríquez died a sudden death.[238] After receiving the Extreme Unction, his body was laid to rest in a mass grave as a charity, since he was penniless and nobody paid for a burial.[239] Only Paris and Rosa Enríquez, his unrecognized daughter who would later claim that he had been poisoned, mourned his death.[239] LegacyAcademic research

Salvador Brau's take of Enríquez's life in 1854

With its goal finally accomplished, the high class of San Juan did its part to erase Enríquez's presence from the collective memory of Puerto Rico.[239] His loyalty to the Crown was also ignored by the same authorities that he fervently served in life and his role in history eventually faded from the records.[239] Throughout the following centuries Enríquez's work became fragmented, with the bulk remaining obscure.[1] Locally, authors Salvador Brau, Arturo Morales Carrión and José Luis González played a role introducing him to Puerto Rican literature, while his figure was established within the education system by 1922's Historia de Puerto Rico.[1] Internationally, the early accounts of his life reflect their source, with British versions depicting him as a pirate while the Spanish ones describe his accomplishments. An example was published in 1940 by historian Jean O. McLachlan who lived in British India, who after revising the declarations of the South Sea Company's factors concluded that Enríquez "[should have been] the most famous of the guarda costas" and that he "may have been a desperado".[240] McLachlan contends that Enríquez was an ex-slave who got his fortune by "betraying a gentleman to the Inquisition" and used this to become a privateer.[240] He then further goes on to claim that Enríquez was "given a gold medal and the title of Don […] as a result of giving presents to the royal officials and even to His Catholic Majesty".[240] A direct contrast is established in the eleventh volume of Historia general de España y América, a collaboration written by several professors of the University of Córdoba and the University of Seville detailing the history of Spain, which asserts that "[of] all the Spanish corsairs, the most accomplished one was the Puerto Rican Miguel Henríquez", whom they describe as a "famous and feared […] mythological figure in the Caribbean" during his lifetime.[241][242] A more systematic approach was taken by Vegan historian Ángel López Cantós, who studied Enríquez's life and whereabouts for decades.[1] The process of rediscovering the privateer's past took several years of research, during which his life's work was slowly retrieved from the contemporary documents that survive in the General Archive of the Indies.[1] Afterwards, López published several books based on his examination, including two biographies, a novel titled Mi Tío, Miguel Enríquez (lit. "My uncle, Miguel Enríquez") and the historical compilation Historia y poesía en la vida de Miguel Enríquez (lit. "History and poetry in the life of Miguel Enríquez").[1] In 2011, professor Milagros Denis Rosario of City University of New York published a socio-historical analysis for Universidad del Norte, where the role that race played in the recognition of those involved in fending off the 1797 British attack of San Juan was examined, as part of its thesis the document discussed the role and background of similar individuals in the Military history of Puerto Rico.[243] Among the issues explored were the circumstances of Enríquez's downfall, which are discussed within the framework set by López Cantós and Brau, leading to the author's conclusion that the backlash of the higher classes "represents a clear example of how the [18th century] Puerto Rican society was not ready to accept this kind of individual."[243] In her doctoral dissertation in psychology, Miriam Biascoechea Pereda argues that Enríquez is the first recorded instance of an "incipient national identity" among locals, emphasizing that he acted on behalf of "his people [so they] could survive in lieu of Spain's blatant neglect of this forlorn colony."[244] This author states that the "Puerto Rican nation was born with a Mulatto and Caribbean flair" due to his "powerful and influential personality" which "was feared by all, even by the Spanish Monarch, for his bravery and might."[244] Presence in arts and mediaDespite the success of his career, the presence of Enríquez in modern Puerto Rican culture has been eclipsed by his clandestine counterpart, Roberto Cofresí.[245] However, this process of romanticization began during the 20th century. Teacher, journalist and writer Enrique A. Laguerre wrote a novel dedicated to his memory, titled Miguel Enríquez: Proa libre sobre mar gruesa (lit. "Miguel Enríquez, free life in a heavy sea").[246] Enríquez, who became the wealthiest man on the archipelago during the first half of the 18th century, is now considered to have been the first Puerto Rican economic force and entrepreneur.[2] Historian and author Federico Ribes Tovar considered him a "financial genius".[247] Proposals to name a large cargo transport ship after him have been pursued, but with no success so far.[1] In 2010 the ruins of a chapel that he built within El Plantaje in 1735, named Ermita de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria, was recognized as an historic monument by the Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico.[248] Though the examples remain scarce, Enríquez has inspired other kinds of media. In 2007, the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture published a series of comic books named ICePé.cómic, with the 12th volume being Miguel Enríquez, corsario puertorriqueño (lit. "Miguel Enríquez, Puerto Rican corsair"). In 2016, Raúl Ríos Díaz published the eponymous short documentary Miguel Enríquez, which combined his own research with Cantós' previous work, later winning a Gold Peer Award for best direction and the public preference vote at the San Juan Fine Arts Film Festival.[249] As part of the Ibero-American branch of promotion for Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag, Ubisoft published an "affinity test" that allowed players to gauge their relation to certain historical figures, among whom was Enríquez, who was listed under both variants of his name.[250] He was played by actor Modesto Lacén in the San Juan National Historic Site/Northern Light Productions documentary El legado de una Isla: Las fortificaciones del Viejo San Juan which debuted on March 7, 2017. In 2021, painter Antonio Martorell unveiled an acrylic piece titled Don Miguel Enríquez (Corsario del rey) as part of his "Entretelas Familiares" series, depicting the corsair in full military uniform while a scene involving a sloop and schooner sailing at sea develops in the background.[251] This exhibit illustrated seventy-six portraits dealing with family, friendship and societal dynamics at large and was featured at the Museo de las Américas in Old San Juan until September 2022.[252] See also

Notes

References

Bibliography

Further reading

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||