|

African Slave Trade Patrol

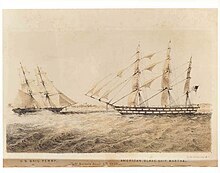

African Slave Trade Patrol was part of the Blockade of Africa suppressing the Atlantic slave trade between 1819 and the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861. Due to the abolitionist movement in the United States, a squadron of U.S. Navy warships and cutters were assigned to catch slave traders in and around Africa. In 42 years about 100 suspected slave ships were captured.[1][2] OperationsOriginThe first American squadron was sent to Africa in 1819, but after the ships were rotated out there was no constant American naval presence off Africa until the 1840s. In the two decades between, very few slave ships were captured as there were not enough United States Navy ships to patrol over 3,000 miles of African coastline, as well as the vast American coasts and the ocean in between. Also, the slavers knew that if they hoisted a Spanish or Portuguese flag they could easily escape pursuit. Congress made it difficult for the navy to keep a small force in Africa until 1842 when the Webster–Ashburton Treaty with the United Kingdom was signed. Commodore Matthew C. Perry was sent to command the Africa Squadron again after serving as the commander in 1821 aboard USS Shark. His arrival marked the beginning of America's growing effectiveness in the suppression though the overall victories were insignificant compared to the Royal Navy's West Africa Squadron in the same period. The British captured hundreds of slave ships and fought several naval battles; their success was largely due to the superior size of their navy and supply bases located in Africa itself. The combined efforts of both the British and the United States successfully freed thousands of slaves but the trade continued on and the operation was expanded to the West Indies, Brazil and the Indian Ocean. The Brazil Squadron, the West Indies Squadron, the East India Squadron and the later Home Squadron were all responsible for capturing at least a few slavers each.[3][2] Revenue Cutter Service PatrolsOn 1 January 1808, a law making the slave trade from Africa illegal went into effect. Revenue cutters were charged with enforcing this law. On 29 June 1820, the Dallas captured the 10-gun brig General Ramirez carrying 280 African slaves off of St. Augustine, Florida. On 25 March, the Alabama captured three slave ships. By 1865, revenue cutters had captured numerous slavers and freed nearly 500 slaves. Capture of SpitfireOn 13 June 1844, the brig USS Truxtun was placed back in commission with Commander Henry Bruce in charge. Two weeks later, she sailed down the Delaware River and passed between the capes and into the Atlantic. After visiting Funchal, Madeira, the ship joined the African Station off Tenerife in the Canary Islands. For the next sixteen months, Truxtun patrolled off West Africa, visiting Monrovia, Liberia and Sierra Leone, where slaves were freed. Truxtun also sailed to Maio islands of Santiago, and São Vicente. The Americans captured only one slaver on their cruise in 1845, the New Orleans schooner named Spitfire. The vessel was caught on the Rio Pongo in Guinea and was taken without incident. Though she was only about 100 tons, she carried 346 slaves. The Americans also discovered that she had landed 339 slaves near Matanzas, in Cuba, the year before. Commander Bruce reported that "between her decks, where the slaves were packed, there was not room enough for a man to sit, unless inclining his head forward; their food was half a pint of rice per day, with one pint of water. No one can imagine the sufferings of slaves on their passage across, unless the conveyances in which they are taken are examined. A good hearty negroe costs but twenty dollars, or thereabouts, and brings from three to four hundred dollars in Cuba." The capture of Spitfire gave the American Navy the incentive to increase the strength of the Africa Squadron. The ship was also fitted out and used in anti-slavery operations. On October 30, 1845, Truxtun weighed anchor at Monrovia, and she headed west towards Gosport Navy Yard, which she reached on November 23. She was then decommissioned on November 28.[4]

Capture of Ann D. Richardson and IndependenceThe brig USS Perry served in the South Atlantic with the Brazil Squadron beginning in 1847. Perry got under way from Philadelphia on May 16, 1847, with specific orders to patrol between Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and Buenos Aires, Argentina. Lieutenant John A. Davis was informed that suspected slavers in the American barque Ann D. Richardson were bound for the coast of Africa under false papers. Perry then seized the ship off Rio de Janeiro on December 16. Two days later, she also seized the American brig Independence. Investigation proved that both ships had been engaged in the slave trade, and both were sent to New York City as prizes. The captain of Independence was outraged about his arrest and even petitioned Commodore George W. Storer, but to no avail. USS Perry returned to Norfolk on July 10, 1849, and was decommissioned there four days later. She later served in Africa again, but only for a short while, after which she sailed back to New York.[2][3] Capture of MarthaOne of the Americans' more significant victories in the operation was the capture of the slave ship Martha. On June 6 of 1850, Perry, under Lieutenant Davis, discovered the large rigged ship Martha off Ambriz while she was standing in to shore. Soon after, as Perry came within gun range, Lieutenant Davis and his men witnessed some of Martha's crew throwing a desk over the side while raising the American flag. The slavers apparently did not realize that the brig was a United States Navy vessel until an officer and a few enlisted men were dispatched, at which time they lowered the American ensign and raised a Brazilian flag. When the officer reached Martha's deck, the captain denied having any papers, so a boat was sent after the desk, which was still floating, and all the necessary evidence was recovered. After that the slave trader admitted to Davis that he was a United States citizen and his ship was equipped for blackbirding. A hidden deck was found below with a large amount of farina and beans, over 400 wooden spoons, and metal devices used to restrain slaves. It was also learned that the captain of Martha was expecting a shipment of 1,800 Africans when Perry appeared. Martha was sent with a prize crew to New York City where she was condemned. The slaver captain paid 3,000 dollars to escape prison.[5] Capture of Nightingale of Boston The 1,066 ton clipper ship USS Nightingale originally sailed as part of the American merchant fleet as Nightengale of Boston[citation needed] in China, before trade in that region became unprofitable during the 1850s. She then became a known slave ship until being seized at St. Thomas on January 14, 1861, by the sloop-of-war USS Saratoga. Saratoga's Captain later described the slaver;

The slaves were freed and landed at Monrovia in Liberia but not before 160 of them died from African fever aboard Saratoga. The sickness also spread to the crew. The Captain, who was called the "Prince of Slavers",[citation needed] and his Spanish second mate escaped Nightingale while she was anchored of St. Thomas. Lieutenant John J. Guthrie, who was from North Carolina, then a slave state, was suspected of freeing the two and letting them escape justice. The clipper eventually served in the American Civil War as the storeship USS Nightingale in the Gulf Blockading Squadron. Ultimately, she was abandoned at sea in 1893, while under a Norwegian flag.[6] End of operationsUnited States Navy operations against the slave trade largely ceased in 1861 with the outbreak of the American Civil War. Navy vessels were recalled from all over the world and reassigned to the Union blockade of southern ports. By the end of the Civil War, the African slave trade on the Atlantic had diminished further, though overland slave trading continued into the 1900s, primarily in North Africa and Central Africa. U.S. Navy officers who served in Africa between 1820 and 1861 received the "African Slave Patrol" campaign streamer.[2][3][7][8] Vessels seized Africa Squadron

Brazil Squadron

Home Squadron

See also

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||