|

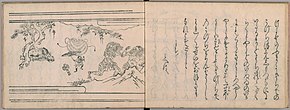

Otogi-zōshi

Otogi-zōshi (御伽草子) are a group of about 350 Japanese prose narratives written primarily in the Muromachi period (1392–1573). These illustrated short stories, which remain unattributed, together form one of the representative literary genres of the Japanese medieval era. OverviewOtogi-zōshi is a general term for narrative literature written between the Muromachi period (approximately 1336–1573) and the beginning of the Edo period (1603–1867).[1] The term originates with a mid-Edo collection of 23 stories, titled Otogi Bunko (御伽文庫) or Otogi-zōshi (御伽草紙/御伽草子).[1] It later came to denote other works of the same genre and period.[1] Modern scholarship sometimes distinguishes between "true" otogi-zōshi, covering only the 23 works included in the aforementioned collection, and other works that it instead terms Muromachi-jidai monogatari (室町時代物語) or chūsei shōsetsu (中世小説).[1] ListThe 23 tales covered by the narrow definition are:

Under the broad definition, there are around 500 surviving examples of otogi-zōshi.[1] Most are around 30–40 pages in length,[1] and are of uncertain date.[1] Their authors are also largely unknown,[1] but whereas Heian and Kamakura monogatari were almost all composed by members of the aristocracy, these works were composed by not just aristocrats but also Buddhist monks, hermits, educated members of the warrior class.[1] Some of the later otogi-zōshi may have been written by members of the emerging urban merchant class.[1] Similarly, the works' intended readership was probably broader than the monogatari of earlier eras.[1] They therefore have a wide variety of contents and draw material from various literary works of the past.[1] Based on their contents, scholars have divided them into six genres:[1]

Kuge-monoKuge-mono are tales of the aristocracy.[1] They mark a continuation of the earlier monogatari literature,[1] and are noted for the influence of The Tale of Genji.[1] Many of them are rewritten or abridged versions of earlier works.[1] Among the romantic works in this sub-genre are Shinobine Monogatari (忍音物語) and Wakakusa Monogatari (若草物語),[1] and most end sadly with the characters cutting themselves off from society (hiren tonsei (悲恋遁世)).[1] Categories Otogi-zōshi have been broken down into multiple categories: tales of the aristocracy, which are derived from earlier works such as The Tale of Genji; religious tales; tales of warriors, often based on The Tale of the Heike, the Taiheiki, The Tale of the Soga and the Gikeiki (The Tale of Yoshitsune); tales of foreign countries, based on the Konjaku Monogatarishū. The most well-known of the tales, however, are retellings of familiar legends and folktales, such as Issun-bōshi, the story of a one-inch-tall boy who overcomes countless obstacles to achieve success in the capital. Origins of the term otogi-zōshiThe term otogi literally means 'companion', with the full name of the genre translating to 'companion tale'. This designation, however, did not come into use until 1725, when a publisher in Osaka released a set of 23 illustrated booklets titled Shūgen otogibunko (Fortuitous Companion Library). As other publishers produced their own versions of Shūgen otogibunko, they began referring to the set of tales as otogi-zōshi. Gradually the term came to describe any work from the Muromachi or early Edo period that exhibited the same general style as the tales in Shūgen otogibunko. History of otogi-zōshi scholarshipOtogi-zōshi came to the attention of modern literary historians in the late 19th century. For the most part, scholars have been critical of this genre, dismissing it for its perceived faults when compared to the aristocratic literature of the Heian and Kamakura periods. As a result, standardized Japanese school textbooks often omit any reference to otogi-zōshi from their discussions of medieval Japanese literature. Recent studies, however, have contradicted this critical stance, highlighting the vitality and inherent appeal of this underappreciated genre. The term chusei shosetsu ('medieval novels'), coined by eminent scholar Ichiko Teiji, attempts to situate the tales within a narrative continuum. List of otogi-zōshi

ReferencesWorks cited

Further reading

External links |