|

Slavery in Morocco

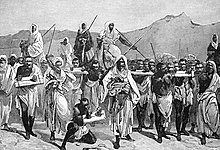

Slavery existed in Morocco since antiquity until the 20th century. Morocco was a center of the Trans-Saharan slave trade route of enslaved Black Africans from sub-Saharan Africa until the 20th century, as well as a center of the Barbary slave trade of Europeans captured by the Barbary pirates until the 19th century. The open slave trade was finally suppressed in Morocco in the 1920s. The haratin and the gnawa have been referred to as descendants of former slaves. Slave tradeAfrican slave tradeFrom the 7th century during the Middle Ages until the early 20th century, Morocco was a center of the Trans-Saharan slave trade of enslaved Africans along the route from Timbuktu to the slave market in Marrakesh, from which they were transported to the rest of Morocco and the Mediterranean world as a whole.[2] In accordance with the Islamic law that Muslims were free to enslave non-Muslims, African tribes who converted to Islam captured non-Muslim people and exported them along the trade route along the coast north toward Morocco. During the Almoravid dynasty (1040–1147) the trade route exported weapons and textiles from Spain in the north to Senegal south of the Sahara, in exchange for gold, ivory, salt and slaves from the non-Islamic areas south of Senegal to Morocco, al-Andalus in Spain and the Mediterranean world.[3] As a spoil of war after defeating the Songhai Empire, sultan Isma‘il ibn Sharif of Morocco was sent thousands of Sub-Saharan slaves from Timbuktu every year, which he then added to his massive army of black-African slaves and Haratin slave-soldiers named the Black Guard (or Abid al-Bukhari). They converted to Islam under the Arabs and Berbers[4] and were forcibly recruited into the Moroccan army by Ismail Ibn Sharif (Sultan of Morocco from 1672 to 1727) to consolidate power.[5] The Trans-Saharan slave route from the city of Timbuktu mainly went to the city of Marrakesh in Morocco, which was known as a big center of the Mediterranean market of African slaves from the 7th century onward, and kept being so for over thousand years, until Morocco became a French protectorate in the 20th century.[2] In the 19th century, between 3500 and 4000 African slaves were trafficked to Morocco via the Trans-Saharan slave trade every year; by the 1880s, they were still 500 yearly.[6] Most concubines in Morocco were black, as they were more easily acquired in the local markets due to continuous yearly supply from the trans-Saharan slave trade.[7] European slave tradeFrom the 16th to the 18th centuries, Ottoman North Africa was a center of the Barbary slave trade where European ships and coastal villages along the Mediterranean was raided by Barbary pirates. Along with Algiers and other provinces of Ottoman North Africa, Morocco was also a center for the slave trade. Sometimes these slave raids or razzias went beyond beyond the Mediterranean, and even places to the north like Ireland was raided once. American shipping in the Mediterranean was also predated upon.[8] The majority of slaves traded across the Mediterranean region were predominantly of African and European origin from the 7th to 15th centuries.[9] In the 15th century, Ethiopians sold slaves from western borderland areas (usually just outside the realm of the Emperor of Ethiopia) or Ennarea.[10] From the 16th century until the early 19th century, Morocco was also a center of the Barbary slave trade of Europeans captured by barbary pirates in the Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea. Barbary corsairs and crews from the quasi-independent[11] North African Ottoman provinces of Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, and the independent Sultanate of Morocco under the Alaouite dynasty (the Barbary Coast) were the scourge of the Mediterranean.[12] Capturing merchant ships and enslaving or ransoming their crews provided the rulers of these nations with wealth and naval power. The Trinitarian Order, or order of "Mathurins", had operated from France for centuries with the special mission of collecting and disbursing funds for the relief and ransom of prisoners of Mediterranean pirates. According to Robert Davis, between 1 and 1.25 million Europeans were captured by Barbary pirates and sold as slaves between the 16th and 19th centuries.[13] FunctionFemale slaveryFemale slaves were primarily used as either domestic servants, or as concubines (sex slaves), often a combination of the two.[14] Female house slaves were frequently sexually exploited and often used as an initiation of men in to sex.[15] The sex slave-concubines of rich urban men who had given birth to the son of their enslaver were counted as the most privileged, since they became an Umm al-walad and became free upon the death of their enslaver; the concubine of a Beduoin mainly lived the same life as the rest of the tribal members and the women of the family.[16] Female domestic slaves lived a hard life and reproduction among slaves was low; it was noted that the infant mortality was high among slaves, and that female slaves were often raped in their childhood and rarely lived in their forties, and that poorer slave owners often prostituted them.[16] The most famous use of concubines took place within the royal harem. According to the writings of the French diplomat Dominique Busnot, Sultan Moulay Ismail had at least 500 concubines and even more children. A total of 868 children (525 sons and 343 daughters) were recorded in 1703, with his seven-hundredth son being born shortly after his death in 1727, by which time he had well over a thousand children.[17][18] This is widely considered among the largest number of children of any human in history. Many of his concubines are only fragmentary documented. As concubines, they were slave captives, sometimes from Europe. One of them, an Irishwoman by the name Mrs. Shaw, was brought to his harem after having been enslaved and was made to convert to Islam when the Sultan wished to have intercourse with her, but was manumitted and married off to a Spanish convert when the Sultan grew tired of her; the Spanish convert being very poor, she was described by contemporary witnesses as reduced to beggary.[19][20] Other slave concubines became favorites and as such were allowed some influence, such as an Englishwoman called Lalla Balqis.[19] Another favorite was a Spanish captive renamed Al-Darah, mother to Moulay Ismail's once favorite son that he himself educated: Moulay Mohammed al-Alim; and to Moulay Sharif. Around 1702, Al-Darah tragically died strangled by Moulay Ismail whom Lalla Aisha had made believe she had betrayed him.[21] It is widely believed that part of the motive for her disgrace was that she pushed[21] him to kill a co-concubine and her son to elevate the chances of her own son of becoming the monarch. Male slaveryMale slaves were used as laborers, eunuchs or soldiers. The conditions of slavery could be very hard, and male slaves were made to work in hard labor in heavy construction, in quarries, and as galley slaves, rowing the galleys, including the galleys of the barbary corsair pirates themselves.[22] Choosing slaves to undergo the grooming process was highly selective in the Moroccan empire. There are many attributes and skills slaves can possess to win the favour and trust of their masters. When examining master/slave relationships we are able to understand that slaves with white skin were especially valued in Islamic societies. Mode of acquisition, as well as age when acquired heavily influenced slave value, as well as fostering trusting master-slave relationships. Many times, slaves acquired as adolescents or even young adults became trusted aides and confidants of their masters. Furthermore, acquiring a slave during adolescence typically leads to opportunities for education and training, as slaves acquired in their adolescent years were at an ideal age to begin military training. In Islamic societies, it was normal to begin this process at the age of ten, lasting until the age of fifteen, at which point these young men would be considered ready for military service. Slaves with specialised skills were highly valued in Islamic slave societies. Christian slaves were often required to speak and write in Arabic. Having slaves fluent in English and Arabic was a highly valued tool for diplomatic affairs. Bi-lingual slaves like Thomas Pellow used their translating ability for important matters of diplomacy. Pellow himself worked as a translator for the ambassador in Morocco. The perhaps most famous slave military force was the Black Guard, also known as ‘Abīd al-Dīwān "slaves of the diwan", Jaysh al-‘Abīd "the slave army", and ‘Abid al-Sultan "the sultan’s slaves")[23] were the corps of black-African slaves and Haratin slave-soldiers assembled by the 'Alawi sultan of Morocco, Isma‘il ibn Sharif (reigned 1672–1727).[24] They were called the "Slaves of Bukhari" because Sultan Isma‘il emphasized the importance of the teachings of the famous imam Muhammad al-Bukhari, going so far as to give the leaders of the army copies of his book.[25] This military corps, which was loyal only to the sultan, was one of the pillars of Isma'il's power as he sought to establish a more stable and more absolute authority over Morocco.[26]: 230–231 Over the course of the later 18th century and the 19th century their role in the military was progressively reduced and their political status varied between privilege and marginalization. Their descendants eventually regained their freedom and resettled across the country. The Black Guard was dissolved in 1912. Slave laborers were also used on the building construction of the Kasbah of Moulay Ismail. AbolitionAbolition came gradual for different categories of slaves. Abolition of the Barbary slave tradeThe slave trade of Europeans ended after the Barbary wars in the early 19th century. On 11 October 1784, Moroccan pirates seized the American brigantine Betsey.[27] The Spanish government negotiated the freedom of the captured ship and crew; however, Spain advised the United States to offer tribute to prevent further attacks against merchant ships. The United States Minister to France, Thomas Jefferson, decided to send envoys to Morocco and Algeria to try to purchase treaties and the freedom of the captured sailors held by Algeria.[28] Morocco was the first Barbary Coast State to sign a treaty with the United States, on 23 June 1786. This treaty formally ended all Moroccan piracy against American shipping interests. Specifically, article six of the treaty states that if any Americans captured by Moroccans or other Barbary Coast States docked at a Moroccan city, they would be set free and come under the protection of the Moroccan State.[29] The Barbary slave trade from Morocco against the ships of other nations also diminished following the Barbary war of the early 19th century. Barbary piracy was eradicated after the Second Barbary war. Abolition of African slave trade and slaveryThe Trans-Saharan slave trade with Africans were ended by the French Colonial authorities in 1923, but the slavery as such persisted long into the 20th century. The Trans-Saharan slave trade with Africans continued after the Barbary slave trade of Europeans diminished. In 1842 sultan Abd al-Rahman of Morocco made a statement defending slavery by stating that slavery was something "all sects and nations have agreed from the time of the sons of Adam".[30] In 1883, Morocco was given an official suggestion by the British Foreign Office to ban slave trade, but Morocco refused to introduce such a ban.[31] In the late 19th century the Sultan of Morocco stated to Western diplomats that it was impossible for him to ban slavery because such a ban would not be enforcable, but the British asked him to ensure that the slave trade in Morocco would at least be handled discreet and away from the eyes of foreign wittnesses.[32] There was no organized internal abolition movement in Morocco. However, slavery in Morocco attracted attention by the abolition movement in the West. Both foreign diplomats as well as foreign abolitionists were active in Morocco. The Anti-slavery International reported about the slavery in the 1880s. Petitions where sent by British representatives to the Moroccan monarch, appealing for the abolition of slavery. On 31 January 1884, the representative of the Moroccan monarch, Muhammed Bargash, answered the British representative Sir J. Drummond Hay that it was impossible to abolish slavery since it would be contrary to Islamic law; but that the slaves where mainly used for light domestic work to serve Muslim women, who because of sex segregation were subjected to harem seclusion and could not leave their homes, and that the slaves were content and well treated, and would not want to be free themselwes:

In 1884, the British and the French governments banned their own citizens and employees in Morocco to own slaves.[31] Between 1912 and 1956, Morocco was colonised by France, which effectively ended the open slave trade in Morocco. In 1923 the French colonial authorities officially banned the slave trade and closed the slave markets in Morocco.[2] While the slave trade was banned, slavery as such was never banned. However, when the slave markets were closed and open slavery visually disappeared from the public eye, slavery was considered to be de facto abolished.[2] In practice the slave trade continued illegally at least two decades after the abolition of the slave trade in 1923.[2] Slavery as such continued in private, mainly in the form of domestic servants. However, during the decades after 1923, slavery gradually diminished in Morocco since changing attitudes made it less common to acquire slaves, and more common to manumit already existing slaves. In the 1930s France reported to the Advisory Committee of Experts on Slavery that slavery had been abolished in all French territories in Africa, including Morocco, and Spain reported that they had abolished the slave trade in Morocco, but avoided mentioning the institution of slavery as such in their report.[34] House slaves were however still used in private homes in Morocco in the 1930s.[14] By 1952 the majority of the existing slaves in Morocco were reportedly kidnapped as children, and when this was said to be against Islamic law, the speed of the manumissions increased. During the second quarter of the 20th century until the 1950s most families manumitted their slaves, which in this time period where mostly female house slaves.[15] Former female slaves (tata) often continued to work in the household of their former owners or in another family in exchange for food and shelter; they worked as cooks or arata (ritual inviters), or sought refuge in charitable institutions.[15] Destitute former female slaves could also turn to prostitution in order to survive.[15] When Morocco won its independence in 1956, slavery was said to be essentially confined to the Household slaves of the Royal Harem.[2] The traditional Royal Harem still existed during the reign of king Hassan II of Morocco (r. 1961–1999): the Royal Harem included forty personal concubines (who by Islamic law were by definition slaves) as well as an additional forty concubines who the king had inherited by his father; additional concubines who worked as domestic servants in the Royal Harem, as well as male slaves performing other positions such as chauffeurs in the Royal Household.[35] The slaves of the Royal Household were descended from enslaved ancestors inherited within the household.[35] The Royal Harem was dissolved by Mohammed VI of Morocco when he ascended to the throne in 1999.[35][36] After abolitionThe slave descentants, the Haratin have been, and still commonly are socially isolated in some Maghrebi countries, living in segregated, Haratin-only ghettos. They converted to Islam under the Arabs and Berbers[4] and are commonly perceived as an endogamous group of former slaves or descendants of slaves.[4][5] Gallery

See alsoReferences

External links

|