|

Sunny South (clipper)

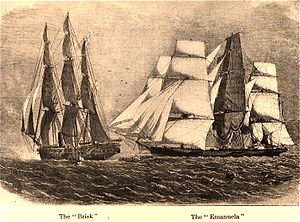

13°02′53″S 45°11′42″E / 13.048°S 45.195°E Sunny South, an extreme clipper, was the only full-sized sailing ship built by George Steers, and resembled his famous sailing yacht America, with long sharp entrance lines and a slightly concave bow. Initially, she sailed in the California and Brazil trades.[2] Sold in 1859 and renamed Emanuela (or Manuela),[1] she was considered to be the fastest slaver sailing out of Havana.[4] The British Royal Navy captured Emanuela off the coast of Africa in 1860 with over 800 slaves aboard.[5] The Royal Navy purchased her as a prize and converted her into a Royal Navy store ship, Enchantress.[1] She was wrecked in the Mozambique Channel in 1861. ConstructionSunny South was built for the China trade, but she was too small to be profitable on that route. The timbers of her wooden hull were somewhat lighter than usual for a ship of her size, and diagonally strapped with iron. Sunny South's topsides were black, and a scaly sea serpent was her figurehead.[2][4] A description of her launch (7 September 1857) in the New York Times stated that a large number of people were in attendance, and praised her beauty and fine sailing characteristics, as was characteristic of press coverage of that time.[6] Voyages to California and BrazilOn her maiden voyage in 1854, Sunny South made a 143-day passage from New York to San Francisco under Capt. Michael Gregory,[7] putting in at Rio de Janeiro. She made unusually good time in the Pacific on this passage between the Equator and the Golden Gate. She then sailed to Hong Kong in ballast in 51 days, with a 102-day return passage to New York City, arriving in January 1856.[2] Sunny South began sailing to Brazilian ports with her voyage of March 1, 1856. Her fastest passage to Rio was 37 days; her three other trips ranged from 40 to 46 days. The three return passages from Santos, Brazil ranged from 41 to 49 days.[2] On April 14, 1858, Sunny South arrived in New York from Santos, transporting a portion of the crew of the clipper ship John Gilpin, which was lost off the Falkland Islands. The crew members had been dropped off in Bahia, Brazil, after their rescue by the British ship Hertfordshire.[2] Capture of EmanuelaIn 1859, Sunny South was sold to Havana for $18,000.[1] She was renamed Emanuela (or Manuela) and put into the Atlantic slave trade. Sunny South/Emanuela was one of three American-built clipper ships known to have engaged in the slave trade. (The other two were Nightingale and Haidee.) [4] Clipper ships were the fastest sailing ships available in the 1850s, and Howard I. Chapelle asserts in The Search for Speed Under Sail that Sunny South had the reputation of being the fastest slaver sailing out of Havana.[4] On March 5, 1860, Emanuela left Havana, allegedly bound for Hong Kong, under the Chilean flag.[1] On August 10, 1860, the British screw sloop-of-war HMS Brisk captured Emanuela with 846 slaves aboard,[5] in the Mozambique Channel.[1] At 11:30 am Brisk, under Captain Algernon de Horsey,[8] bearing the flag of Rear-Admiral the Hon. Sir Henry Keppel, K. C. B., was running to the northward in the Mozambique Channel when she sighted a ship in the haze with many sails set, which proceeded to change course as if attempting to avoid contact. Brisk made sail and steam, and reached a speed of 11 1/2 knots as she pursued Emanuela.[9] Even so, it was at least four hours later before she could draw close enough to fire a shot across Emanuela's bow, board her, and take the slaver captain and officers into custody. Brisk then put into Pomoni in possession of Emanuela to make arrangements to replace the slaver crew with a prize crew.[10][11] The speed of this slave ship under sail was sufficiently memorable that years later, in a 1914 novel, The Mutiny of the Elsinore, Jack London had an old sailor character exclaim,

This comment concurs with the opinion of an eyewitness. The explorer John Hanning Speke was aboard Brisk as a passenger, and described the capture scene in The Discovery of the Source of the Nile. According to Speke, if the wind had been more favorable, Sunny South could have outsailed Brisk and escaped, despite Brisk having the advantage of an auxiliary steam engine.[10] Speke inspected the slave ship and bore witness in his writings regarding the appalling and inhumane conditions on board. When Speke boarded Manuela as she lay in Pomoni Harbor, he saw half-starved people below decks, mostly children, along with a few old women who lay dying in "the most disgusting ferret box atmosphere." Other slaves who had the strength were ripping open the ship's hatches and scrambling for the salted fish packed beneath.[10] The slaver's voyage had been stopped in its first few days, and the 7-foot (2.1 m) slave deck had adequate ventilation.[11] As a result, many of the slaves proved healthy despite their lack of food and the horrible stench of the ship. After the prize crew washed down the slave deck as best they could, the two ships proceeded to Mauritius.[10] According to Speke, the slaves he encountered were mostly from the Wahiyow tribe. They had been captured during local wars and sold to Arab traders, taken to the coast, and then taken to Manuela in dhows. The slaves were half starved because they had been kept for nearly a week without food while the traders negotiated their deal.[10] The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database says Emanuela picked up slaves at Quirimba on August 10, 1860. Of the 846 slaves who embarked, 105 died en route, and 741 arrived at the first place of landing. Over half were children (appx. 55%); appx. 87% male, 13% female. Of this number appx. 47% were boys, 40% men, 9% girls, and 5% women.[5] Author Charles Dickens, who paid a visit to Manuela six months after its capture, wrote that the ship still smelled horrible despite all attempts to disinfect it. He was told that the crew had been observed dumping Manuela's logs and flag overboard shortly before being boarded.[11] Release of captured slaves and crewThe captain of Brisk, Captain de Horsey was angered by the lack of punishment for Manuela's 45-member slaver crew when they reached shore. An official letter to the Secretary of the Admiralty, dated December 31, 1860, expressed his displeasure:

The freed slaves were put ashore at Mauritius, where they were later hired out to sugar planters.[11] Enchantress Sunny South was taken to Mauritius, where a prize court condemned her. The Royal Navy renamed her Enchantress and used her as a store ship on the coast of Africa, to prevent the ship being purchased by slavers.[1][2][14] Enchantress ran aground on a reef at Mayotte in the Mozambique Channel on 20 February 1861. According to Dickens, she sailed so fast that the crew did not realize they were already eleven miles offshore and standing into danger.[11] The Royal Navy sent HMS Sidon to destroy the wreck by burning.[14] References

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||