|

Volga Bulgaria

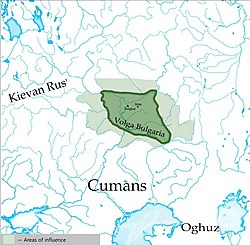

Volga Bulgaria or Volga–Kama Bulgaria (sometimes referred to as the Volga Bulgar Emirate[2]) was a historical Bulgar[3][4][5] state that existed between the 9th and 13th centuries around the confluence of the Volga and Kama River, in what is now European Russia. Volga Bulgaria was a multi-ethnic state with large numbers of Bulgars, Finno-Ugrians, Varangians, and East Slavs.[6] Its strategic position allowed it to create a local trade monopoly with Norse, Cumans, and Pannonian Avars.[7] HistoryOrigin and creation of the stateThe origin of the early Bulgars is still unclear. Their homeland is believed to be situated between Kazakhstan and the North Caucasian steppes. Interaction with the Hunnic tribes, causing the migration, may have occurred there, and the Pontic–Caspian steppe seems the most likely location.[8] Some scholars propose that the Bulgars may have been a branch or offshoot of the Huns or at least Huns seem to have been absorbed by the Bulgars after Dengizich's death.[9] Others however, argue that the Huns continued under Ernak, becoming the Kutrigur and Utigur Hunno-Bulgars.[10] These conclusions remain a topic of ongoing debate and controversy among scholars. The Bulgars were an Oghuric people[11][12] who settled north of the Black Sea. During their westward migration across the Eurasian steppe, they came under the overlordship of Khazars, leading other ethnic groups, including Finno-Ugric and Iranic as well as other Turkic peoples.[11] In about 630 they founded Old Great Bulgaria, which was destroyed by the Khazars in 668. Kotrag, following the death of his father, began to extend the influence of his Bulgars to the Volga River. He is remembered as the founder of Volga Bulgaria.[13][14] They reached Idel-Ural in the eighth century, where they became the dominant population at the end of the 9th century, uniting other tribes of different origin who lived in the area.[15] However, some Bulgar tribes under the leader Asparukh moved west from the Pontic-Caspian steppes and eventually settled along the Danube River.,[16] in what is now known as Bulgaria proper, where they created a confederation with the Slavs, adopting a South Slavic language and the Eastern Orthodox faith. However, Bulgars in Idel-Ural eventually gave birth to Chuvash people. Unlike Danube Bulgars, Volga Bulgars did not adopt any language. The Chuvash language today is the only Oghuric language that survived and it is the sole living representative of the Volga Bulgar language.[17][18][19][20] Most scholars agree that the Volga Bulgars were initially subject to the Khazar Khaganate. This fragmented Volga Bulgaria grew in size and power and gradually freed itself from the influence of the Khazars. Sometime in the late 9th century, unification processes started and the capital was established at Bolghar (also spelled Bulgar) city, 160 km south of modern Kazan. However, complete independence was reached after Khazaria's destruction and conquest by Sviatoslav in the late 10th century; thus, Bulgars no longer paid tribute to it.[21][22] Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur named the Volga Bulgar people as Ulak.[23] Conversion to Islam and further statehoodVolga Bulgaria adopted Islam as a state religion in 922 – 66 years before the Christianization of Kievan Rus'. In 921 Almış sent an ambassador to the Caliph requesting religious instruction. The next year an embassy returned with Ibn Fadlan as secretary. A significant number of Muslims already lived in the country.[24] The Volga Bulgars attempted to convert Vladimir I of Kiev to Islam; however Vladimir rejected the notion of Rus' giving up wine, which he declared was the "very joy of their lives".[25] Commanding the Volga River in its middle course, the state controlled much of trade between Europe and Asia prior to the Crusades (which made other trade routes practicable). Bolghar, was a thriving city, rivalling in size and wealth the greatest centres of the Islamic world. Trade partners of Bolghar included from Vikings, Bjarmland, Yugra and Nenets in the north to Baghdad and Constantinople in the south, from Western Europe to China in the East. Other major cities included Bilär, Suar (Suwar), Qaşan (Kashan) and Cükätaw (Juketau). Modern cities Kazan and Yelabuga were founded as Volga Bulgaria's border fortresses. Some of the Volga Bulgarian cities have still not been found, but they are mentioned in old East Slavic sources. They are: Ashli (Oshel), Tuxçin (Tukhchin), İbrahim (Bryakhimov), Taw İle. Some of them were ruined during and after the Golden Horde invasion.[citation needed] Volga Bulgaria played a key role in the trade between Europe and the Muslim world. Furs and slaves were the main goods in this trade, and the Volga Bulgarian slave trade played a significant role. People taken captive during the viking raids in Western Europe, such as Ireland, could be sold to Moorish Spain via the Dublin slave trade[26] or transported to Hedeby or Brännö in Scandinavia and from there via the Volga trade route to Russia, where slaves and furs were sold to Muslim merchants in exchange for Arab silver dirham and silk, which have been found in Birka, Wollin and Dublin;[27] initially this trade route between Europe and the Abbasid Caliphate passed via the Khazar Kaghanate,[28] but from the early 10th century onward it went via Volga Bulgaria and from there by caravan to Khwarazm, to the Samanid slave market in Central Asia and finally via Iran to the Abbasid Caliphate.[29] Slavic pagans were also enslaved by Vikings, Magyars, and Volga Bulgars, who transported them to Volga Bulgaria, where they were sold to Muslim slave traders and continued to Khwarezm and the Samanids, with a minor part being exported to the Byzantine Empire.[30] This was a major trade; the Samanids were the main source of Arab silver to Europe via this route,[29] and Ibn Fadlan referred to the ruler of the Volga Bulgar as "King of the Saqaliba" because of his importance for this trade.[29] The Rus' principalities to the west posed the only tangible military threat. In the 11th century, the country was devastated by several raids by other Rus'. Then, at the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, the rulers of Vladimir (notably Andrew the Pious and Vsevolod III), anxious to defend their eastern border, systematically pillaged Volga Bulgarian cities. Under Rus' pressure from the west, the Volga Bulgars had to move their capital from Bolghar to Bilär.[citation needed] DeclineFrom the beginning of the 13th century, the Volga Bulgars were subject to multiple raids from the East Slavic principalities as multiple skirmishes took place for control of the Unzha River which was an important commercial route. In 1220, the Grand Duke Yuri II of Vladimir captured Ustiug and besieged the important Bulgar town of Aşlı. The consequence of this was that Vladimir-Suzdal gained access to Volga Bulgaria's northern trade routes and hindered the means of the Bulgars acquiring fur.[31] The Nikon Chronicle also details that following this, Yuri II began amassing a large force of Rus' for an even larger campaign against the Bulgars. The Bulgars would send entreaties and proposals for peace but these were all rejected. Yuri travelled with his army to Omut where further entreaties for peace were received from the Bulgars however these were still rejected. However, by the time Vasilko Konstantinovich of Rostov arrived, Yuri accepted an offer of gifts and agreed to adhere to an earlier peace treaty with the Bulgars that was agreed under the rule of his father, Vsevolod the Big Nest.[31] In September 1223 near Samara an advance guard of Genghis Khan's army under the command of Uran, son of Subutai Bahadur,[disputed – discuss] entered Volga Bulgaria but was defeated in the Battle of Samara Bend.[citation needed] In 1236, the Mongols returned and in five years had subjugated the whole country, which at that time was suffering from internal war [citation needed]. Henceforth Volga Bulgaria became a part of the Ulus Jochi, later known as the Golden Horde. It was divided into several principalities; each of them became a vassal of the Golden Horde and received some autonomy. By the 1430s, the Khanate of Kazan was established as the most important of these principalities.[31] LanguageVolga Bulgar language was a Turkic language. The only extant member of the Oghuric group that is still spoken today is the Chuvash language. The language persisted in the Volga region up until the 13th or 14th century. Although there is no direct evidence, some scholars believe it gave rise to modern Chuvash language[17][18][19][20] while others support the idea that Chuvash is another distinct Oghur Turkic language.[32] Italian historian and philologist Igor de Rachewiltz noted a significant distinction of the Chuvash language from other Turkic languages. According to him, the Chuvash language does not share certain common characteristics with Turkic languages to such a degree that some scholars consider Chuvash as an independent branch from Turkic and Mongolic. The Turkic classification of Chuvash was seen as a compromise solution for classification purposes.[33] Definition of verbs in Volga Bulgar[34][35]

Volga Bulgars left some inscriptions in tombstones. There are few surviving inscriptions in the Volga Bulgar language, as the language was primarily an oral language and the Volga Bulgars did not develop a writing system until much later in their history.[36] After converting to Islam, some of these inscriptions were written using Arabic letters while the use of the Orkhon script continued. Mahmud al-Kashgari provides some information about the language of the Volga Bulgars, whom he refers to as Bulghars. Some scholars suggest Hunnic had strong ties with Bulgar and to modern Chuvash[37] and classify this grouping as separate Hunno-Bulgar languages.[38] However, such speculations are not based on proper linguistic evidence, since the language of the Huns is almost unknown except for a few attested words and personal names. Scholars generally consider Hunnish as unclassifiable.[39][40][41][42] Numbers and Vocabulary in Volga Bulgar[35][34][43][44][45][46][47]

Mahmud al-Kashgari also provides some examples of Volga Bulgar words, poems, and phrases in his dictionary.. However, Mahmud al-Kashgari himself wasn't a native speaker of Volga Bulgar. Despite its limitations, Mahmud al-Kashgari's work remains an important source of information about the Volga Bulgar language and its place within the broader Turkic language family.

Coats of arms of Volga Bulgaria during Tsarist RussiaIvan III was also called the "Prince of Bulgaria". The mention of the Bulgarian land has been present in the royal title since 1490. This refers to Volga Bulgaria.

It is known that the Bulgarian coat of arms figure was used to designate the Bulgarian Kingdom and in the Great Seal of Tsar John IV. The seal was a "lion walking" (which is confirmed by the seals of the Volga Bulgarians found by archaeologists). On the coats of arms and seals of the Russian tsars, the lands of Volga Bulgaria were represented on a green field by a silver walking lamb with a red banner divided by a silver cross; the shaft is gold.[53] The erroneous perception of the beast on the Bulgarian coat of Arms in the Royal Titular as a lamb is explained by the poor quality of the reproduction of the image. In the "Historical Dictionary of Russian Sovereigns ..." by I. Nekhachin (ed. by A.Reshetnikov, 1793), the Bulgarian coat of arms is described as follows: "Bulgarian, in a blue field, a silver lamb wearing a red banner." Over time, the colour of the shield changed to green. In the Manifesto on the full coat of arms of the Empire (1800), the Bulgarian coat of arms is described as follows: "In a green field it has a white Lamb with a golden radiance near its head; in its right front paw it holds a Christian banner." The description of the coat of arms, approved in 1857: "The Bulgarian coat of arms: a silver lamb walking in a green field, with a scarlet banner, on which the cross is also silver; the shaft is gold."

DemographicsA large part of the region's population included Turkic groups such as Sabirs, Esegel, Barsil, Bilars, Baranjars, and part of the obscure[54] Burtas (by ibn Rustah). Modern Chuvash claim to descend from Sabirs, Esegels, and Volga Bulgars.[55] Another part comprised Volga Finnic and Magyar (Asagel and Pascatir) tribes, from which Bisermäns probably descend.[56] Ibn Fadlan refers to Volga Bulgaria as Saqaliba, a general Arabic term for Slavic people. Other researches tie the term to the ethnic name Scythian (or Saka in Persian).[57] Over time, the cities of Volga Bulgaria were rebuilt and became trade and craft centres of the Golden Horde. Some Volga Bulgars, primarily masters and craftsmen, were forcibly moved to Sarai and other southern cities of the Golden Horde. Volga Bulgaria remained a centre of agriculture and handicraft.[citation needed] Gallery

See also

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Volga Bulgaria.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||