|

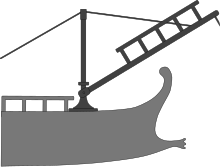

Corvus (boarding device)

The corvus (Latin for "crow" or "raven") was a Roman ship mounted boarding ramp or drawbridge for naval boarding, first introduced during the First Punic War in sea battles against Carthage. It could swivel from side to side and was equipped with a beak-like iron hook at the far end of the bridge, from which the name is figuratively derived, intended to anchor the enemy ship. The corvus was still used during the last years of the Republic. Appian mentions it being used on August 11th 36BC, during the battle of Mylae, by Octavian's navy led by Marcus Agrippa against the navy of Sextus Pompeius led by Papias.[citation needed] DescriptionIn Chapters 1.22-4-11 of his History, Polybius describes this device as a bridge 1.2 m (4 ft) wide and 10.9 m (36 ft) long, with a small parapet on both sides. The engine was probably used in the prow of the ship, where a pole and a system of pulleys allowed the bridge to be raised and lowered. There was a heavy spike shaped like a bird's beak on the underside of the device, which was designed to pierce and anchor into an enemy ship's deck when the boarding bridge was lowered. This allowed a firm grip between the vessels and a route for the Roman legionaries (who served as specialized naval infantry called marinus) to cross onto and capture the enemy ship. In the 3rd century BCE, Rome was not a naval power and had little experience in sea combat. Before the First Punic War began in 264 BCE, the Roman Republic had not campaigned outside the Italian Peninsula. The Republic's military strength was in land-based warfare, and its main assets were the discipline and the courage of the Roman soldiers. The boarding bridge allowed the Romans to use their infantry advantage at sea, therefore helping to overcome the Carthaginians' superior naval experience and skills. The Romans' application of boarding tactics worked by winning several battles, most notably those of Mylae, Sulci, Tyndaris and Ecnomus. Despite its advantages, the boarding bridge had a serious drawback in that it could not be used in rough seas; the stable connection of two bobbing ships endangered both ships' structures. When operating in rough conditions, the device became useless as a tactical weapon.[1] The added weight on the prow may have also compromised the ship's navigability, and it has been suggested that this instability led to Rome losing almost two entire fleets during storms in 255 and 249 BCE.[1] Those losses may have contributed to Rome abandoning the boarding bridge in ship design over time. However, a different analysis suggests that the added weight did not threaten ship stability. JW Bonebakker, formerly Professor of Naval Architecture at TU Delft, used an estimated corvus weight of one ton to conclude that it was "most probable that the stability of a quinquereme with a displacement of about 250 m3 (330 cu yd) would not be seriously upset" when the bridge was raised.[1] Regardless of the reasons, it appears that Rome was no longer using the corvus at the end of the First Punic War. As Rome's ship crews became more experienced, Roman naval tactics also improved; accordingly, the relative utility of using the corvus as a weapon may have diminished. The device is not mentioned in period sources after the Battle of Ecnomus, and apparently, the Battle of the Aegates Islands decided the war in 241 BCE and was won without it. By 36 BCE, at the Battle of Naulochus, the Roman navy had been using a different kind of device to facilitate boarding attacks, a harpoon and winch system known as the harpax, or harpago. Modern interpretationsThe design of the corvus has undergone many transformations throughout history. The earliest suggested modern interpretation of the corvus came in 1649 by German classicist Johann Freinsheim. Freinsheim suggested that the bridge consisted of two parts, one section measuring 24 ft (7.3 m) and the second being 12 ft (3.7 m) long. The 24 ft (7.3 m) section was placed along the prow mast and a hinge connected the smaller 12 ft (3.7 m) piece to the mast at the top. The smaller piece would have been the actual gangway as it could swing up and down, and the pestle was attached to the end.[2] The classical scholar and German statesman B.G. Niebuhr ventured to improve the interpretation of the corvus and proposed that the two parts of Freinsheim’s corvus simply needed to be swapped. By applying the 12 ft (3.7 m) side along the prow mast, the 24 ft (7.3 m) side could be lowered onto an enemy ship by means of the pulley.[3] The German scholar K.F. Haltaus hypothesized that the corvus was a 36 ft (11 m) long bridge with the near end braced against the mast via a small oblong notch in the near end that extended 12 ft (3.7 m) into the bridge. Haltaus suggested that a lever through the prow mast would have allowed the crew to turn the corvus by turning the mast. A pulley was placed on the top of a 24 ft (7.3 m) mast that raised the bridge in order to use the device.[4] The German classical scholar Wilhelm Ihne proposed another version of corvus that resembled Freinsheim’s crane with adjustments in the lengths of the sections of the bridge. His design placed the corvus twelve feet above the deck and had the corvus extend out from the mast a full 36 ft (11 m) with the base of the near end connected to the mast. The marines on deck would then be forced to climb a 12 ft (3.7 m) ladder to access to the corvus.[5] The French scholar Émile de St. Denis suggested the corvus featured a 36 ft (11 m) bridge with the mast hole set 12 ft (3.7 m) from the near end. The design suggested by de St. Denis, however, did not include an oblong hole and forced the bridge to travel up and down the mast completely perpendicular to the deck at all times.[6] The next step in that direction occurred in 1956, when the historian H.T. Wallinga published his dissertation The Boarding-Bridge of the Romans. It suggested a different full-beam design for the corvus, which became the most widely accepted model among scholars for the rest of the twentieth century. Wallinga's design included the oblong notch in the deck of the bridge to allow it to rise at an angle by the pulley mounted on the top of the mast.[7] Not everybody, however, has accepted the idea that the Romans invented and used the corvus as a special device. In 1907, William W. Tarn postulated that the corvus never existed.[8] Tarn believed that the weight of the bridge would be too much for the design of the Roman ships to remain upright. He suggested that once the corvus was raised, the ship would simply roll over and capsize by the weight added by the corvus.[9] Tarn believed that the corvus was simply an improved version of an already-existing grapnel pole, which had been used in Greece as early as 413 BC.[10] Notes

References

External links |