|

Nemi ships  The Nemi ships were two ships, of different sizes, built under the reign of the Roman emperor Caligula in the 1st century AD on Lake Nemi. Although the purpose of the ships is speculated upon, the larger ship was an elaborate floating palace, which contained quantities of marble, mosaic floors, heating and plumbing, and amenities such as baths. Both ships featured technology thought to have been developed historically later. It has been stated that the emperor was influenced by the lavish lifestyles of the Hellenistic rulers of Syracuse and Ptolemaic Egypt. Recovered from the lake bed in 1929, the ships were destroyed by fire in 1944 during World War II. The larger ship was 73 m (240 ft) in length, with a beam of 24 m (79 ft). The other ship was 70 m (230 ft) long, with a beam (width) of 20 m (66 ft). Location Lake Nemi (Italian: Lago di Nemi, Latin: Nemorensis Lacus) is a small circular volcanic lake in the Lazio region of Italy, 30 km (19 mi) south of Rome. It has a surface of 1.67 km2 (0.64 sq mi) and a maximum depth of 33 m (108 ft). There is considerable speculation regarding why the emperor Caligula chose to build two large ships on such a small lake. From the size of the ships it was long held that they were pleasure barges, though, as the lake was sacred, no ship could sail on it under Roman law (Pliny the Younger, Litterae VIII-20) implying a religious exemption.[1] Caligula particularly favoured the Egyptian Isis cult which he had established in Rome and also supported that of Diana Nemorensis, whom, in the Roman tradition of syncretism, he likely viewed as an aspect of Isis.[2] Situated on opposite sides of the lake and atop the crater walls are the towns of Genzano and Nemi. Genzano was dedicated by the Romans to the goddess Cynthia, a cult associated with that of Diana Nemorensis. Nemi did not exist in Roman times. The name Nemi derives from the Latin nemus Aricinum (grove of Ariccia), Ariccia being an important nearby town associated with the worship of Diana and the god Virbius (the Latin name for Hyppolytus, a young man whom Diana loved). Located at Nemi are the ruins of an ancient temple dedicated to Diana, which was connected by the Via Virbia to the Via Appia (the Roman road between Rome and Brindisi).[3] During the time of the Roman Empire, the area around Genzano was used by wealthy Roman citizens for its clean air, uncontaminated water and cooler temperatures during the hot summer months. The lake has its own microclimate and is protected from wind by the crater walls. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Lord Byron, and Charles Gounod all lived in Nemi and noted the reflection of the Moon, seen in the centre of the lake during summer. This phenomenon is the source of the Roman name for the lake, Speculum Dianae (Diana's Mirror).[3] Recovery Local fishermen had long been aware of the existence of the wrecks, and had explored them and removed small artefacts, often using grappling hooks to pull up pieces, which they sold to tourists.[4] In 1446, His Eminence Prospero Cardinal Colonna and Leon Battista Alberti followed up on the stories regarding the remains and discovered them lying at a depth of 18.3 metres (60 ft), which at that time was too deep for effective salvage. They damaged the ships by using ropes with hooks to tear planks from them. Alberti learned little more than the type of wood and that it was covered in lead sheathing. In 1535, Francesco De Marchi dived on the wreck using a diving helmet.[5] His finds included bricks, marble paving stones, bronze, copper, lead artefacts, and a great number of timber beams. From material recovered he added the knowledge that mortise and tenon joints had been used in their construction. Despite the successful salvage of entire structures and parts, there was no academic interest in the ships, so no further research was performed. The objects recovered were lost and their fate remains unknown.[3]  By 1827, interest had revived and it had become a widespread belief that earlier material recovered either had been part of a temple to Diana or was from the villa of Julius Caesar cited by Suetonius. Annesio Fusconi built a floating platform from which to raise the wrecks. Several of his cables broke, and he called a halt until he could find stronger cables. When he returned, he found that the locals had dismantled his platform to make wine barrels. This led him to abandon the project.[3] In 1895, with the support of the Ministry of Education, Signor Eliseo Borghi began a systematic study of the wreck site and discovered that the site contained two wrecks instead of the one expected.[6] Among the material Borghi recovered was the bronze tiller head of one of the rudders and many bronze heads of wild animals. Borghi placed all of his finds in his own museum and offered to sell the collection to the Government. The timbers he recovered were discarded and lost, while no contextual referencing was documented for any of his finds. Felice Barnabei, director general of the Department of Antiquity and Fine Art, claimed all of the artefacts for the National Museum and submitted a report requesting the recovery cease because of the "devastation of the two wrecks". An engineer from the Regia Marina (the Italian Royal Navy) surveyed the site to determine the feasibility of recovering the two ships intact. The engineer concluded that the only viable way was to partially drain the lake.[3] In 1927, Il Duce Benito Mussolini, President of the Council of Ministers, ordered Guido Ucelli to drain the lake and recover the ships. With the help of the Regia Marina (Royal Italian Navy), the Regio Esercito (Royal Italian Army), industry and private individuals, an ancient Roman underground water conduit linking the lake to farms outside the crater was reactivated. The conduit was connected to a floating pumping platform on 20 October 1928 and the lake level began dropping. By 28 March 1929, the water level had dropped 5 m (16 ft), and the first ship (prima nave) broke the surface. By 10 June 1931, the prima nave had been recovered and the second ship (seconda nave) was exposed. By this time the water level had dropped more than 20 m (66 ft) with over 40,000,000 m3 of water removed. As a result of the weight reduction, on 21 August 1931, 500,000 m3 of mud erupted from the underlying strata causing 30 hectares (74 acres) of the lake floor to subside. Work ceased and, while the risks of continuing the project were debated, the lake began refilling. As the seconda nave had already partly dried out, the submersion caused considerable damage. On 10 November 1931, the Minister of Public Works ordered the project and all research abandoned.[3] On 19 February 1932, the Navy Ministry, which had been a partner in the recovery, petitioned Mussolini to resume the project. Joining with the Ministry of Education, they received permission to take over responsibility for it, and pumping to drain the lake recommenced on 28 March. Around this time a small boat was found, about 10 m (33 ft) long, with a pointed bow and a square stern. It had been loaded with stones in order to sink it and is believed to be contemporaneous with the ships. Technical problems prevented the recovery of the seconda nave until October 1932. A purpose-built museum constructed over both ships was inaugurated in January 1936.[3] Construction   Both vessels were constructed using the Vitruvian method, a shell-first building technique used by the Romans.[1]

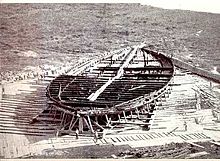

The species selected were known to work well for Mediterranean shipbuilding. Shipwrights used oak for the keel and the end posts, the ship’s spine. They also used oak for the internal framing, the through-beams, and the stanchions. Naturally curved timbers were employed for the posts and frames. Mediterranean shipbuilders prized softwoods like pine and fir for their flexibility and resistance to water. They provided the planking on the exterior hull and the thickened timbers on the exterior and interior, the wales and stringers, all of which had to be bent into place.[7] The hull had been sheathed in three layers of lead sheathing to protect the timbers from shipworms; as there are none in freshwater lakes, this design feature was not only costly of effort and weight but useless. It is evidence that the ships' hulls were constructed following standardised Roman shipbuilding techniques rather than being purpose-built. The topside timbers were protected by paint and tarred wool and many of their surfaces decorated with marble, mosaics, and gilded copper roof tiles. There was a lack of coordination between the structure of the hull and that of the superstructures, which suggests that naval architects designed the hulls, and civil architects then designed the superstructure to use the space available after the hulls were completed.[1] After their recovery, the ships' hulls were found to be completely empty and unadorned. They were steered using 11.3 m (37 ft)-long quarter oars, with the seconda nave equipped with four, two off each quarter and two from the shoulders, while the prima nave was equipped with two. Similar pairs of steering leeboards appear frequently in early 2nd-century depictions of ships.[8] The seconda nave was almost certainly powered by oars, as structural supports for the rowing positions protrude along the sides of the hull. The prima nave had no visible means of propulsion so was likely towed to the centre of the lake when in use.[3] A lead pipe found on one of the wrecks had Property of Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus stamped on it while many tiles had dates of manufacture. Together it leaves little doubt as to when the ships were built or for whom.[8] Suetonius describes two ships built for Caligula; "...ten banks of oars...the poops of which blazed with jewels...they were filled with ample baths, galleries and saloons, and supplied with a great variety of vines and fruit trees." It is reasonable to speculate that the Nemi ships were equipped to a comparable standard. One year after being launched, following the assassination of Caligula (24 January 41),[3] the ships were stripped of precious objects, overballasted and then intentionally sunk. Prima naveThe first ship recovered was 70 m (230 ft) long, with a beam (width) of 20 m (66 ft). The hull was divided into three "active" or main sections. The general shape of the hull appears wider at the stern and narrower at the bow; in fact, the main section is not amidships but is displaced towards the stern. The superstructures appear to have been made of two main blocks of two buildings each, connected by stairs and corridors, built on raised parts of the deck at either end. This distribution gives the ship a discontinuous look and has no similarity to any other ancient construction.[1] Seconda naveThe second ship recovered was the larger at 73 m (240 ft) in length and with a beam of 24 m (79 ft). The superstructure appears to have been made with a main section amidships, a heavy building at the stern and a smaller one at the prow. Although nothing remains of the stern and prow buildings their existence is indicated by the shorter spacing of the decks supporting cross beams and distribution of ballast.[1] The arrangement of the seconda nave superstructures is comparable to that of the shrines depicted on an Isian lamp held by the Museum of Ostia. If not coincidental, this is further evidence of worship of Isis rather than Diana.[1] Technology  The discovery proved that the Romans were capable of building large ships. Before the recovery of the Nemi ships, scholars often ridiculed the idea that the Romans were capable of building a ship as big as some ancient sources reported the Roman grain carriers were.[9] For centuries large numbers of lead bars had been found on the Mediterranean seabed, and there was debate over whether they were anchor stocks or not. It was argued by some that iron-tipped wooden anchors secured by ropes were not heavy enough to be effective, so they had to have metal stocks, and there was considerable academic controversy over the issue. The Nemi ships, constructed during the transition period when iron anchors were replacing wooden ones, were the first Roman wrecks found to have intact anchors, and confirmed that the lead bars were indeed anchor stocks.[10] Two types of anchor were found, one of oak with iron-tipped flukes and a stock of lead and another of iron with a folding timber stock that closely matched the design of the Admiralty pattern anchor, re-invented in 1841. In the 1960s, a similar anchor was found in Pompeii, and in 1974 another was found buried near Aberdarewllyn in Gwynedd, Wales. These further discoveries confirmed that these technologically advanced anchors were a standard Roman design.[10] Both ships had several hand-operated bilge pumps that worked like a modern bucket dredge, the oldest example of this type of bilge pump ever found. The pumps were operated by what may have been the oldest crank handles yet discovered;[11] however, the reconstruction of the cranked pump from fragments, including a wooden disk and an eccentric peg, has been dismissed as "archaeological fantasy".[12] Piston pumps (ctesibica machina: Vitruvius X.4?7) supplied the two ships with hot and cold running water via lead pipes. The hot water supplied baths while the cold operated fountains and supplied drinking water. This plumbing technology was later lost and only re-discovered in the Middle Ages. Modern experimental archaeology has demonstrated that the Nemi ships could also have had central heating systems of hypocaust type.[13] Each ship contained a rotating platform. One was mounted on caged bronze balls and is the earliest example of the thrust ball bearing previously believed to have been first envisioned by Leonardo da Vinci but only developed much later. Previous Roman ball bearing finds (used for water wheel axles in thermal baths) had a lenticular shape. The second platform was almost identical in design but used cylindrical bearings. Although consensus is that the platforms were meant for displaying statues, it has also been suggested that they may have been meant for deck cranes used to load supplies.[14] DestructionThe ships were destroyed by fire during World War II on the night of 31 May 1944.[15] At that time, Allied forces were pursuing the retreating German army northward through the Alban Hills toward Rome. On 28 May, a German artillery unit set up a four-gun battery 150 metres from the Museum where the two ships were housed. The Germans drove out the museum custodians, who were forced to hide in nearby caves. The presence of German troops around the building attracted Allied counter-battery fire. On the evening of the fire, several shells of the United States Army hit the museum around 8:00 p.m. Approximately two hours later, at 10 p.m., significant flames were observed coming from the museum. The German forces left the area on 3 June 1944 and when the caretakers returned to the museum, they found the ships reduced to ashes. When news of the destruction reached Rome a few days thereafter, an Italian-American commission of inquiry was established to ascertain accountability for the fire. The official report submitted in Rome later that year (July 1944) characterized the tragedy as "most likely" a deliberate act by German soldiers.[16] Conversely, an editorial released by the head of the German military office responsible for the protection of artworks (Kunstschutz) suggested that the destruction may have resulted from American artillery fire.[17] The true responsibility for the fire remained a subject of prolonged debate, although the narrative attributing blame to German troops was widely accepted and recognized officially at an institutional level. However, recent and comprehensive study conducted by Flavio Altamura and Stefano Paolucci (2023)[18][19] has undertaken a critical review of the findings from the investigations carried out in 1944, utilizing extensive unpublished documentation and modern fire investigation techniques. The analysis reveals the baselessness of the evidence against the German troops and concludes that the only plausible explanation for the fire is that it was caused by impacts from Allied artillery shells. On the same evening as the fire, at least four explosive rounds aimed at a nearby German position accidentally struck the museum, creating significant holes in its roof. However, the role of these explosions in igniting the fire was arbitrarily excluded by the Commission from the earliest stages of their inquiry. The exoneration of Allied artillery relied on illogical arguments that contradicted the opinion of the sole artillery expert among those investigating, who had indicated that grenades were likely responsible for the disaster. By comparing current methodologies in fire investigation, the authors demonstrate that both the dynamics and timing of the blaze align solely with this hypothesis of accidental ignition. The numerous contradictions and inconsistencies identified within testimonial statements and Commission documents indicate that assertions regarding German culpability constituted a convenient narrative shaped by pressures and circumstances surrounding the historical-political context of the Liberation of Italy. Furthermore, alternative accounts concerning potential causes of the disaster proposed over time — ranging from a fire escaping control from evacuees sheltering in the museum to alleged actions by local residents, partisans, or metal thieves[20] — have proven entirely unfounded from both historiographical and factual perspectives. Only the bronzes, a few charred timbers, and some material stored in Rome survived the fire. Because of the destruction, research effectively stopped until the 1980s. The museum was restored and reopened in 1953. One-fifth scale models of the ships were built in the Naples naval dockyard, and these, along with the remaining artefacts, are housed there. In September 2017 a panel made of inlaid marble and mosaic then in the collection of a private owner in New York City was rediscovered by the antiquities restorer and author Dario del Bufalo. Subsequently the New York County District Attorney's Office seized the artefact, which was confirmed to have come from the Nemi Museum, and to have once decorated the floor of Caligula's ship.[21] It had been bought by two American antique dealers, Helen and Nereo Fioratti, from an aristocratic family in the late 1960s, and used since then as the surface of a coffee table in their home. In October it was officially repatriated to Italian authorities.[22][23] Project Diana Photographs, as well as drawings made for the Italian Navy survey and those made by the archaeologist G. Gatti, survived, allowing reconstructions to be made of the two ships. In 1995, the Association Dianae Lacus (Lake of Diana Association) was founded to preserve the culture and history of the Nemi Lake area. The Association initiated Project Diana, which involved constructing a full-size replica of the Roman prima nave (first ship) of Lake Nemi. Since no record is known to exist of the shape and size of the buildings and temples built on the deck, the replica was to be constructed to deck level only and when completed would be moored on the lake in front of the museum. On 18 July 1998, the town council of Nemi voted to fund the construction of the forward section, and work commenced in the Torre del Greco shipyards. This section was completed in 2001 and transported to the Nemi museum, where the rest of the vessel was to be constructed. The estimated final cost of the reconstruction was 7.2 million Euros (US$10.7 million).[3] According to the Association Dianae Lacus website, on 15 November 2003 the large Italian employer and business confederation Assimpresa announced its immediate sponsorship of all timber required for the construction.[24] However, no press releases have been made since 2004, and the association's web site was deleted on 1 October 2011. Original piecesOriginal individual pieces from the Nemi ships that were recovered from Lake Nemi between 1895 and 1932.[25]

See also

References

Sources

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Nemi ships.

41°43′20″N 12°42′6″E / 41.72222°N 12.70167°E

|