|

Lampung language

Lampung or Lampungic (cawa Lampung) is an Austronesian language or dialect cluster with around 1.5 million native speakers, who primarily belong to the Lampung ethnic group of southern Sumatra, Indonesia. It is divided into two or three varieties: Lampung Api (also called Pesisir or A-dialect), Lampung Nyo (also called Abung or O-dialect), and Komering. The latter is sometimes included in Lampung Api, sometimes treated as an entirely separate language. Komering people see themselves as ethnically separate from, but related to, Lampung people. Although Lampung has a relatively large number of speakers, it is a minority language in the province of Lampung, where most of the speakers live. Concerns over the endangerment of the language has led the provincial government to implement the teaching of Lampung language and script for primary and secondary education in the province.[3] ClassificationExternal relationshipLampung is part of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of Austronesian family, although its position within Malayo-Polynesian is hard to determine. Language contact over centuries has blurred the line between Lampung and Malay,[4][5][6] to the extent that they were grouped into the same subfamily in older works, such as that of Isidore Dyen in 1965, in which Lampung is placed inside the "Malayic Hesion" alongside Malayan (Malay, Minangkabau, Kerinci), Acehnese and Madurese.[7] Nothofer (1985) separates Lampung from Dyen's Malayic, but still include it in the wider "Javo-Sumatra Hesion" alongside Malayic, Sundanese, Madurese, and more distantly, Javanese.[8] Ross (1995) assigns Lampung its own group, unclassified within Malayo-Polynesian.[9] This position is followed by Adelaar (2005), who excludes Lampung from his Malayo-Sumbawan grouping—which includes Sundanese, Madurese, and Malayo-Chamic-BSS (comprising Malayic,[a] Chamic, and Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa languages).[5][10]  Among the Javo-Sumatran languages, Nothofer mentions that Sundanese is perhaps the closest to Lampung, as both languages share the development of Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (PMP) *R > y and the metathesis of the initial and medial consonants of Proto-Austronesian *lapaR > Sundanese palay 'desire, tired' and Lampung palay 'hurt of tired feet'.[8] While the Javo-Sumatran/Malayo-Javanic grouping as a whole has been criticized or outright rejected by various linguists,[11][12] a closer connection between Lampung and Sundanese has been supported by Anderbeck (2007), on the basis that both languages share more phonological developments with each other than with Adelaar's Malayo-Chamic-BSS.[13] Smith (2017) notes that Lampung merges PMP *j with *d, which is a characteristic of his tentative Western Indonesian (WIn) subgroup.[14] However, lexical evidence for its inclusion in WIn is scant. Smith identifies some WIn lexical innovations in Lampung, but it is hard to tell whether these words are inherited from Proto-WIn or borrowed later from Malay.[6] While Smith supports its inclusion in the WIn subgroup, he states that the matter is still subject to debate.[6] Dialects

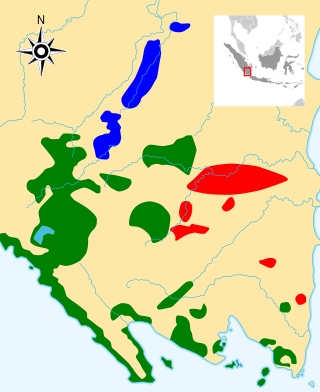

Lampung dialects are most commonly classified according to their realizations of Proto-Lampungic final *a, which is retained in some varieties, but realized as [o] in others.[15][16] This dichotomy leads to the labeling of these as A-dialect and O-dialect, respectively.[17] Walker (1975) uses the names Pesisir/Paminggir for the A-dialect and Abung for the O-dialect,[18] but Matanggui (1984) argues that these are misnomers, as each of them is more commonly associated with a specific tribe instead of the whole dialect group.[17] Anderbeck and Hanawalt use the names Api for Pesisir and Nyo for Abung, after their respective words for 'what'.[5] There are some lexical differences between these dialects,[4] but they are identical in terms of morphology and syntax.[19] Walker (1976) further subdivides Abung into two subdialects: Abung and Menggala, while splitting the Pesisir group into four subdialects: Komering, Krui, Pubian, and Southern.[4] Aliana (1986) gives a different classification, listing a combined total of 13 different subdialects within both groups.[20] Through lexicostatistical analysis, Aliana finds that the Pesisir dialect of Talang Padang shares the most similarities with all dialects surveyed; in other words, it is the least divergent among Lampung varieties, while the Abung dialect of Jabung is the most divergent.[21] However, Aliana does not include Komering varieties in his survey of Lampung dialects, as he notes that some people do not consider it part of Lampung.[22] Hanawalt (2007) largely agrees with Walker,[23] only that he classifies Nyo, Api, and Komering as separate languages rather than dialects of the same language based on sociological and linguistic criteria.[24] He notes that the biggest division is between the eastern (Nyo) and western (Api and Komering) varieties, with the latter forming an enormous dialect chain stretching from the southern tip of Sumatra up north to the downstream regions of Komering River. Some Lampungic-speaking groups (such as the Komering and Kayu Agung peoples) reject the "Lampung" label, although there is some understanding among them that they are "ethnically related to the Lampung people of Lampung Province".[23] While many researchers consider Komering as part of Lampung Api, Hanawalt argues that there is enough linguistic and sociological differences to break down the western chain into two or more subdivisions; he thus proposes a Komering dialect chain, separate from Lampung Api.[24] Demography and statusLike other regional languages of Indonesia, Lampung is not recognized as an official language anywhere in the country, and as such it is mainly used in informal situations.[25] Lampung is in vigorous use in rural areas where the Lampung ethnic group is the majority. A large percentage of speakers in these areas almost exclusively use Lampung at home, and use Indonesian on more formal occasions.[26][27] In the market where people of different backgrounds meet, a mix of languages is used, including local lingua franca like Palembang Malay.[28] Despite it being well alive in rural areas, already in the 1970s, Lampung youths in urban areas preferred to use Indonesian instead.[4] In general, there seems to be a trend of "diglossia leakage" in the bilingual Lampung communities, where Indonesian is increasingly used in domains traditionally associated with Lampung language usage.[26]  Since the early 20th century, the province of Lampung has been a major destination for the transmigration program, which moves people from the more densely populated islands of Indonesia (then Dutch East Indies) to the less densely populated ones.[29][30] The program came to a halt during an interlude following the outbreak of World War II, but the government resumed it several years after Indonesian independence.[29] By the mid-1980s, Lampung people had become a minority in the province, accounting for no more than 15% of the population, down from 70% in 1920.[31] This demographic shift is also reflected in language usage; the 1980 census reported that 78% of the province's population were native speakers of either Javanese, Sundanese, Madurese, or Balinese.[32] As an effort to maintain the indigenous language and "to help define Lampung's identity and cultural symbol", post-New Order era Lampung regional government[b] has made Lampung language a compulsory subject for all students attending primary and secondary educational institutions across the province.[32][33] The state university of Lampung runs a master's degree program in Lampung language study.[34] The university once also held an associate degree in Lampung language study, but the program was temporarily halted in 2007 due to a change in regulation.[33] Nevertheless, the university has announced a plan to launch a bachelor's degree in Lampung language study by 2019.[34] PhonologyVowels

Anderbeck distinguishes four basic vowel phonemes and three diphthongs in the Lampungic cluster. He prefers to analyze the /e/ phoneme described by Walker[36] an allophone of /i/.[35] Similarly, he notes that the /o/ phoneme previously posited for Komering by Abdurrahman and Yallop[37] is better reanalyzed as an allophone of /ə/.[35] The reflection of /ə/ varies widely across dialects, but the pattern is predictable. Western varieties consistently realize ultimate /ə/ as [o]; additionally, penultimate /ə/ also becomes [o] in varieties spoken throughout the Komering river basin. In many Nyo dialects, final /ə/ is reflected as an [o] or [a] if it is followed by /h/ or /ʔ/. In the Nyo dialect of Blambangan Pagar, final /ə/ is realized as [a] only if the previous vowel is also a schwa; otherwise, /ə/ is realized as [ə]. The Melintin subdialect retains the conservative realization of *ə as [ə] in all positions.[38] Nyo varieties differ from the rest of Lampungic isolects by reflecting Proto-Lampungic final *a in open syllable as /o/.[4][16] Later, Nyo varieties also develop the tendency to realize final vowels as diphthongs. Final /o/ is variously realized as [ə͡ɔ], [ow], or similar diphthongs. Most Nyo speakers also pronounce final /i/ and /u/ as [əj] and [əw], respectively.[16] This diphthongization of final vowels in open syllables occurs in all Nyo varieties, except in the Jabung subdialect.[15] Consonants

The occurrence of /z/ is limited to some loanwords.[37] There are various phonetic realizations of /r/ within the Lampungic cluster, but it is usually a velar or uvular fricative ([x], [ɣ], [χ], or [ʁ]) in most dialects.[39] Udin (1992) includes this phoneme as /ɣ/ and states that it is also variously pronounced as [x] or trilled [r].[40] Walker lists /x/ (with a voiced allophone [ɣ] between vocals) and /r/ as separate phonemes for Way Lima subdialect, although he comments that the latter mostly appears in unassimilated loanwords, and is often interchangeable with [x].[36] Abdurrahman and Yallop describe Komering /r/ as an apical trill instead of a velar fricative.[37] The proto-phoneme is variously written as gh, kh, or r (for the variation between the former two, cf. the slogans of TVRI Lampung). In many varieties, some words have their consonants metathesized. Examples include hiruʔ 'cloud' from Proto-Lampungic *rihuʔ, gəral 'name' from PLP *gəlar,[39] and the near-universal metathesis of PLP *hatəluy (from PMP *qateluR) to tahlui 'egg' or similar forms.[41] Another common–yet irregular–phonological change in Lampungic cluster is debuccalization, which occurs in almost all varieties. PLP *p and *t are often targets of debuccalization; *k is less affected by the change.[39] Consonant gemination is also common in Lampung, especially in Nyo and some Api varieties, but almost unknown in Komering. Gemination often happens to consonants preceded by penultimate schwa or historical voiceless nasal (which got reduced to the stop component). Cases of gemination in medial positions have been recorded for all consonants except /ɲ/, /ŋ/, /s/, /w/ and /j/.[39] PhonotacticsThe most common syllable patterns are CV and CVC. Consonant clusters are found in a few borrowed words, and only word-initially. These consonant clusters are also in free variation with sequences separated by schwas (CC~CəC).[36] Disyllabic roots take the form (C)V.CV(C). Semivowels in medial positions are not contrastive with their absences.[42] StressWords are always stressed in the final syllable, regardless whether they are affixed or not. The stress though is very light and can be distorted by the overall phrasal intonation. Partially free clitics, on the other hand, are never stressed except when they appear in the middle of an intonation contour.[42] GrammarPronouns

Like in some Indonesian languages, there is a distinction between the "lower" and "higher" forms of words based on the degrees of formality and the age or status of the speaker relative to the listener, although this distinction is only limited to pronouns and some words.[43] The "lower" forms are used when addressing younger people, or people with close relationship; while the "higher" forms are used when addressing older people or those with higher status.[44] Personal pronouns can act like proclitics or free words. Enclitic pronouns are used to mark possession.[42] When speaking formally, the "higher" forms of pronouns are used instead of clitics.[44] ReduplicationAs with many other Austronesian languages, reduplication is still a productive morphological process in Lampung. Lampung has both full reduplication, which is the complete repetition of a morpheme, and partial reduplication, which is the addition of a prefix to a morpheme consisting of its first consonant + /a/. Some morphemes are inherently reduplicated, such as acang-acang 'pigeon' and lalawah 'spider'.[45] Nouns are fully reduplicated to indicate plurality and variety, as in sanak-sanak 'children' from sanak 'child'[45] and punyeu-punyeu 'fishes' from punyeu 'fish'.[46] Partial reduplication of nouns can convey the same meaning, but this formation is not as productive as full reduplication. More often, partial reduplication is used to signify a similarity between the root word and the derived noun:[e][45]

Complete reduplication of adjectives denotes intensification:[47][48]

Partial reduplication, on the other hand, soften the meaning of an adjective:[47]

Reduplication of verbs signifies "a continuous or prolonged action or state":[49]

Writing system The Latin script (with Indonesian orthography) is usually used for printed materials in the language.[43] However, traditionally, Lampung is written in Rencong script, an abugida, with the Lampung alphabet (Indonesian: aksara lampung or Lampung Api: had Lampung). It has 20 main characters and 13 diacritics.[50] This script is most similar to the Kerinci, Rejang and similar alphabets used by neighboring ethnic groups in southwestern Sumatra. The Rencong script, along with other traditional Indonesian writing systems like the Javanese script, descends from the Kawi script which belongs to the Brahmic family of scripts that originated in India.[43] Lampung script has been proposed for inclusion in the Unicode Standard.[51] See alsoNotes

ReferencesCitations

Bibliography

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||