|

Dextropropoxyphene

Dextropropoxyphene[5] is an analgesic in the opioid category, patented in 1955[6] and manufactured by Eli Lilly and Company. It is an optical isomer of levopropoxyphene. It is intended to treat mild pain and also has antitussive (cough suppressant) and local anaesthetic effects. The drug has been taken off the market in Europe and the US due to concerns of fatal overdoses and heart arrhythmias.[7] It is still available in Australia, albeit with restrictions after an application by its manufacturer to review its proposed banning.[8] Its onset of analgesia (pain relief) is said to be 20–30 minutes and peak effects are seen about 1.5–2.0 hours after oral administration.[3] Dextropropoxyphene is sometimes combined with acetaminophen. Trade names include Darvocet-N, Di-Gesic,[9] and Darvon with APAP (for dextropropoxyphene and paracetamol).[10] The British approved name (i.e. the generic name of the active ingredient) of the paracetamol/dextropropoxyphene preparation is co-proxamol (sold under a variety of brand names); however, it has been withdrawn since 2007, and is no longer available to new patients, with exceptions.[11] The paracetamol combination(s) are known as Capadex or Di-Gesic in Australia, Lentogesic in South Africa, and Di-Antalvic in France (unlike co-proxamol, which is an approved name, these are all brand names). Dextropropoxyphene is known under several synonyms, including:

UsesAnalgesiaDextropropoxyphene is generally considered a weak analgesic, with several studies finding its efficacy is no better than acetaminophen.[12] Like codeine, it is a weak opioid. However, dextropropoxyphene has one-third to one-half of the analgesic activity of codeine.[12] Restless legs syndromeDextropropoxyphene has been found to be helpful in relieving the symptoms of restless legs syndrome.[13][14][15] ContraindicationsDextropropoxyphene is contraindicated in patients allergic to paracetamol (acetaminophen) or dextropropoxyphene, and in alcoholics. It is not intended for use in patients who are prone to suicide, anxiety, panic, or addiction. Side effectsSevere toxicity can occur with small increments above the therapeutic dose including cardiotoxicity, and fatal overdoses. This is especially true when the drug is combined with alcohol.[16] Other side effects include:[17]

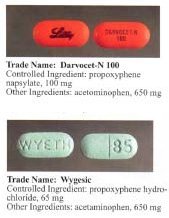

PharmacologyDextropropoxyphene acts as a mu-opioid receptor agonist. It also acts as a potent, noncompetitive α3β4 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist,[18] as well as a weak serotonin reuptake inhibitor. ToxicityOverdose is commonly broken into two categories - liver toxicity (from paracetamol poisoning) and dextropropoxyphene overdose. An overdose of dextropropoxyphene may lead to various systemic effects. Excessive opioid receptor stimulation is responsible for the CNS depression, respiratory depression, aspiration pneumonia, miosis, and gastrointestinal effects seen in propoxyphene poisoning. It may also account for mood- or thought-altering effects. In the presence of amphetamine, propoxyphene overdose increases CNS stimulation and may cause fatal convulsive seizures.[19] In addition, both propoxyphene and its metabolite norpropoxyphene have local anesthetic effects at concentrations about 10 times those necessary for opioid effects. Norpropoxyphene is a more potent local anesthetic than propoxyphene, and they are both more potent than lidocaine.[20] Local anesthetic activity appears to be responsible for the arrhythmias and cardiovascular depression seen in propoxyphene poisoning.[21] Both propoxyphene and norpropoxyphene are potent blockers of cardiac membrane sodium channels, and are more potent than lidocaine, quinidine, and procainamide in this respect.[22] As a result, propoxyphene and norpropoxyphene appear to have the characteristics of a Vaughn-Williams Class Ic antiarrhythmic. These direct cardiac effects include decreased heart rate (i.e. cardiovascular depression), decreased contractility, and decreased electrical conductivity (i.e., increased PR, AH, HV, and QRS intervals). These effects appear to be due to their local anesthetic activity and are not reversed by naloxone.[20][21][23] Widening of the QRS complex appears to be a result of a quinidine-like effect of propoxyphene, and sodium bicarbonate therapy appears to have a positive direct effect on the QRS dysrhythmia.[24] Seizures may result from either opioid or local anesthetic effects.[20] Pulmonary edema may result from direct pulmonary toxicity, neurogenic/anoxic effects, or cardiovascular depression.[21] Balance disorder is possible, with risk of falls from standing height. Available formsPropoxyphene was initially introduced as propoxyphene hydrochloride. Shortly before the patent on propoxyphene expired, propoxyphene napsylate form was introduced to the market. The napsylate salt (the salt of naphthalene-2-sulfonic acid) is claimed to be less prone to non-medical use, because it is almost insoluble in water, so cannot be used for injection. Napsylate also gives lower peak blood level.[25] Because of different molar mass, a dose of 100 mg of propoxyphene napsylate is required to supply an amount of propoxyphene equivalent to that present in 65 mg of propoxyphene hydrochloride. Before the FDA-directed recall, dextropropoxyphene HCl was available in the United States as a prescription formulation with paracetamol (acetaminophen) in ratio from 30 mg / 600 mg to 100 mg / 650 mg (or 100 mg / 325 mg in the case of Balacet), respectively. These are usually named Darvocet. Darvon is a pure propoxyphene preparation that does not contain paracetamol. In Australia, dextropropoxyphene is available on prescription, both as a combined product (32.5 mg dextropropoxyphene per 325 mg paracetamol branded as Di-gesic, Capadex, or Paradex; it is also available in pure form (100 mg capsules) known as Doloxene, however its use has been restricted.[8] Drug testingDetectable levels of propoxyphene/dextropropoxyphene may stay in a person's system for up to 9 days after last dose and can be tested for specifically in nonstandard urinalysis, but may remain in the body longer in minuscule amounts.[26] Propoxyphene does not show up on standard opiate/opioid tests because it is not chemically related to opiates as part of the OPI or OPI 2000 panels, which detect morphine and related compounds. It is most closely related to methadone.[27] HistoryDextropropoxyphene was successfully tested in 1954 as part of US Navy and CIA-funded research on nonaddictive substitutes for codeine.[28] Use in organic synthesisWithout the propionyl group on the oxygen, the non-esterified alcohol precursor of propoxyphene (both enantiomers, known as darvon alcohol and novrad alcohol) have been employed as stoichiometric chiral reagents for asymmetric carbonyl reduction reactions involving aluminium hydride reagents.[29][30] Usage controversy and regulationDextropropoxyphene is subject to some controversy; while many physicians prescribe it for a wide range of mildly to moderately painful symptoms, as well as for treatment of diarrhea, many others refuse to prescribe it, citing limited effectiveness. In addition, the therapeutic index of dextroproxyphene is relatively narrow. Caution should be used when administering dextropropoxyphene, particularly with children and the elderly and with patients who may be pregnant or breastfeeding; other reported problems include kidney, liver, or respiratory disorders, and prolonged use. Attention should be paid to concomitant use with tranquillizers, antidepressants, or excess alcohol. Darvon, a dextropropoxyphene formulation made by Eli Lilly, which had been on the market for 25 years, came under heavy fire in 1978 by consumer groups that said it was associated with suicide. Darvon was never withdrawn from the market, until recently, but Lilly has waged a sweeping, and largely successful, campaign[citation needed] among doctors, pharmacists, and Darvon users to defend the drug as safe when it is used in proper doses and not mixed with alcohol. After determining the risks outweigh the benefits, the USFDA requested physicians stop prescribing the drug. On November 19, 2010, the FDA announced that Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals agreed to withdraw Darvon and Darvocet in the United States, followed by manufacturers of dextropropoxyphene.[31][32] AustraliaIn Australia, both pure dextropropoxyphene capsules (as napsylate, 100 mg), marketed as Doloxene, and combination tablets and capsules (with paracetamol) all containing 32.5 mg dextropropoxyphene HCl with 325 mg paracetamol, which are currently available on prescription were supposed to be withdrawn from 1 March 2012,[33] but Aspen Pharma sought a review in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal which ruled in 2013 that the drugs could be sold under strict conditions.[8] CanadaOn December 1, 2010, Health Canada and Paladin Labs Inc. announced the voluntary recall and withdrawal of Darvon-N from the Canadian market and the discontinuation of sale of Darvon-N.[34] European UnionIn November 2007, the European Commission requested the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to review the safety and effectiveness of dextropropoxyphene based medicines and on 25 June 2009 the EMA recommended a gradual withdrawal throughout the European Union. The EMA's conclusion was based on evidence that dextropropoxyphene-containing medicines were weak painkillers, the combination of dextropropoxyphene and paracetamol was no more effective than paracetamol on its own, and the difference between the dose needed for treatment and a harmful dose (the "therapeutic index") was too small.[35] New ZealandIn February 2010, Medsafe announced Paradex and Capadex (forms of dextropropoxyphene) were being withdrawn from the marketplace due to health issues, and withdrawal in other countries.[36] IndiaOn June 12, 2013, the Indian government suspended the manufacture, sale, and distribution of the drug under Section 26A of the 1940 Drugs and Cosmetic Act.[37] SwedenIn Sweden, physicians had long been discouraged by the medical products agency to prescribe dextropropoxyphene due to the risk of respiratory depression and even death when taken with alcohol.[38] Physicians had earlier been recommended to prescribe products with only dextropropoxyphene and not to patients with a history of substance use disorder, depression, or suicidal tendencies. Products with mixed active ingredients were taken off the market and only products with dextropropoxyphene were allowed to be sold. Dextropoxyphene was de facto narcotica labelled. As of March 2011, all products containing the substance are withdrawn because of safety issues after a European Commission decision.[39][40] At the time, people who drank excessive amounts of alcohol and other substances and take combination dextropoxyphene / acetaminophen (paracetamol) were discussed as needing to take many combination tablets to reach euphoria, because the amount of dextropropoxyphene per tablet is relatively low (30–40 mg). The ingested paracetamol—the other component—may then reach liver toxic levels. In the case of alcoholics, who often already have damaged livers, even a relatively small overdose with paracetamol may produce hepatotoxicity, liver failure, and necrosis. This toxicity with the combination of overdosed dextroproxyphene (with its CNS/respiratory depression/vomit with risk for aspiration pneumonia, as well as cardiotoxicity) and paracetamol-induced liver damage can result in death. United KingdomIn the United Kingdom, preparations containing only dextropropoxyphene were discontinued in 2004.[41] In 2007, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency removed the licence for co-proxamol, also called distalgesic.[42] From then on in the UK, co-proxamol is only available on a named patient basis, for long-term chronic pain and only to those who have already been prescribed this medicine. Its withdrawal from the UK market is a result of concerns relating to its toxicity in overdose (even small overdoses can be fatal), and dangerous reaction with alcohol. Recreational use in the UK is uncommon. Many patients have been prescribed alternative combinations of drugs as a replacement.[11] The motivation for the withdrawal of co-proxamol was the reduction in suicides and a key part of the agency's justification of its decision was based upon studies showing co-proxamol was no more effective than paracetamol alone in pain management.[43][44] The co-proxamol preparations available in the UK contained a subtherapeutic dose of paracetamol, 325 mg per tablet.[45] Patients were warned not to take more than eight tablets in one day, a total dose of 2600 mg paracetamol per day. Despite this reduced level, patients were still at a high risk of overdose; coproxamol was second only to tricyclic antidepressants as the most common prescription drugs used in overdose.[43] Following the reduction in prescribing in 2005–2007, prior to its complete withdrawal, the number of deaths associated with the drug dropped significantly. Additionally, patients have not substituted other drugs as a method of overdose.[46] The decision to withdraw co-proxamol has met with some controversy; it has been brought up in the House of Commons on two occasions, 13 July 2005[47] and on 17 January 2007.[48] Patients have found alternatives to co-proxamol either too strong, too weak, or with intolerable side effects.[citation needed] During the House of Commons debates, it is quoted that originally some 1,700,000 patients in the UK were prescribed co-proxamol. Following the phased withdrawal, this has eventually been reduced to 70,000. However, this apparently is the residual pool of patients who cannot find alternate analgesia to co-proxamol.[citation needed] The safety net of prescribing co-proxamol after license withdrawal from 31 December 2007, on a "named patient" basis where doctors agree a clinical need exists, has been rejected by most UK doctors[citation needed] because the wording that "responsibility will fall on the prescriber" is unacceptable to most doctors. Some patients intend to take the case to the European Court of Human Rights.[49] However, the European Medicines Agency has recently backed the agency's decision, and recommended in June 2009 that propoxyphene preparations be withdrawn across the European Union.[50] On 28 March 2017, NHS Clinical Commissioners announced that co-proxamol will be no longer available under NHS England as part of £400m of spending cuts for prescriptions that are believed to have little or no clinical value.[51] United StatesIn January 2009, an FDA advisory committee voted 14 to 12 against the continued marketing of propoxyphene products, based on its weak pain-killing abilities, addictiveness, association with drug deaths and possible heart problems, including arrhythmia. A subsequent re-evaluation resulted in a July 2009 recommendation to strengthen the boxed warning for propoxyphene to reflect the risk of overdose.[52] Dextropropoxyphene subsequently carried a black box warning in the U.S., stating:

Because of potential for side effects, this drug is on the list for high-risk medications in the elderly.[54] On November 19, 2010, the FDA requested manufacturers withdraw propoxyphene from the US market, citing heart arrhythmia in patients who took the drug at typical doses.[55] Tramadol, which lacks the cardiotoxicity, has been recommended instead of propoxyphene, as it is also indicated for mild to moderate pain, and is less likely to be misused or cause addiction than other opioids.[56] In Popular CultureIn the Stephen King short story collection Night Shift, the final story of the book, "The Woman in the Room", tells a tale in which the main character contemplates and then finally performs a mercy killing using a drug called "Darvon Complex." Use by right-to-die societiesHigh toxicity and relatively easy availability made propoxyphene a drug of choice for right-to-die societies. It is listed in Dr. Philip Nitschke's The Peaceful Pill Handbook and Dr. Pieter Admiraal's Guide to a Humane Self-Chosen Death.[57][58] "With the withdrawal of the barbiturate sleeping tablets from the medical prescribing list, propoxyphene has become the most common doctor-prescribed medication used by seriously ill people to end their lives."[57] See alsoReferences

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||